We learn, remember, forget… What can memory actually do? And can we outsmart it?

21. 05. 2025

Just one cubic millimeter of the human brain can hold about as much data as 1,400 high-performance computers. But how does our memory actually work? Why is it easier for us to recall an embarrassing moment from childhood than a book we read last week? And how can we “hack” memory to our advantage? Find out in our article first published in the 1/2025 issue of A / Easy Magazine.

In the Inside Out movie, memories look like differently colored marbles stored in the brain, in Harry Potter, they appear as wispy threads of liquid silver. In reality, memories don’t have a solid form. Just like all memory traces, they emerge from changes in how nerve cells communicate at their connections – synapses. The ability to adjust the strength of these connections is called synaptic plasticity, and it’s what allows us to remember, learn, and forget.

Human memory is very different from computer memory. While digital data stays the same once it’s saved, memory traces in the brain are always changing – they fade, get stronger, or shift in meaning. That’s why our memories are far from an accurate reflection of reality. Even if you’re convinced you remember a lunch date with a friend down to the last detail, what your brain actually stores are just the highlights: the rude server, the flat soda, an absolutely divine burger. Your brain fills in the rest – correctly or not.

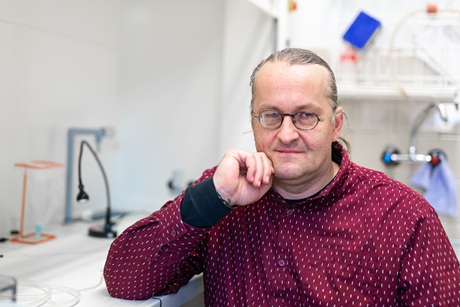

And each time we recall a memory, it gets slightly altered and rewritten. “That’s how false memories can easily form – vivid recollections of things that never happened, or of someone else’s experience that we remember as our own,” says neuroscientist Aleš Stuchlík from the Institute of Physiology of the Czech Academy of Sciences (CAS).

Memory drawers

Memory can be classified by the type of information it stores. Episodic memory retains events, semantic memory stores knowledge, procedural memory contains skills, and spatial memory helps us navigate our surroundings. Then there’s prospective memory, which holds our plans for the future. Each type is encoded in different parts of the brain.

Aleš Stuchlík from the Institute of Physiology of the CAS. (CC)

So how does a sensation become a memory? First, the stimulus passes through our senses and enters sensory (ultrashort-term) memory. A sort of imprint is retained in the cerebral cortex for up to two seconds. If the brain deems the stimulus important, it’s passed on to short-term memory, where it lasts for a few seconds to a minute. Short-term memory has a limited capacity – just five to nine items – so it doesn’t hold much more than a single phone number. During sleep especially, the memory trace is transferred via a process called consolidation into long-term memory, where it can remain for hours, days, or even a lifetime.

When the brain hits delete

Where’s my phone? And what’s the wi-fi password again? At times, forgetting things can feel like our worst enemy. But it’s actually essential for healthy brain function. “It’s a highly adaptive form of neuroplasticity. The brain filters information this way to avoid overload. So the act of forgetting isn’t a flaw – it’s a necessity,” Stuchlík explains. Taking care of this memory clean-up are, for instance, microglia – tiny amoeba-like cells that traverse the brain and consume dysfunctional synapses between neurons.

|

THE MAGIC OF CONTEXT Ever walk into another room and suddenly forget why you went there? You’re not alone. Scientists call this common phenomenon the “doorway effect” – your attention gets redirected to new stimuli in the new environment, sidelining your original intentions. Going back to where you started can often jog your memory. That’s because memories are tied to context – it’s easier to recall something when the setting matches the one in which the memory was formed. |

The natural process of forgetting was first studied by German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus in the late 19th century. He invented 2,300 nonsensical syllables and memorized series of them, recording how long he could retain them in his mind. Based on this experiment, he developed the forgetting curve, which shows how fast we forget new information unless we review it.

According to the curve, we forget the most within minutes of cramming. Roughly half of the information memorized is gone within an hour. After the first day, the rate of forgetting slows. After a week, about a quarter of what we learned remains – and that portion tends to stick around for a while. You can “hack” this process by reviewing. The best route to take is to go over the studied material on the same day you learned it, then again on the second, seventh, and twelfth day.

And what slips away from memory most often? People’s names. Some studies suggest we forget 95 percent of them within five seconds of being introduced. Numbers and vocabulary are also hard to retain. On the other hand, cringeworthy school cafeteria incidents stick with us for years. That’s because the brain prioritizes emotionally charged memories – especially negative ones. “From a neurobiological point of view, the purpose of this filtering is survival. If we’ve had a stressful experience in the past, the brain prepares us in this way to avoid similar situations in the future,” Stuchlík explains.

Masterminds?

He could recite entire volumes of poetry in languages he didn’t understand and rewrite complex mathematical formulas after just a few seconds of looking at them. Everything he ever committed to memory stayed with him for life. The brain of Russian journalist Solomon Shereshevsky fascinated the world in his time. People with similarly extraordinary memory abilities are known as mnemonists. Their talents may be linked to synesthesia, a perceptual condition in which sensory experiences become cross-wired – for instance, people may see music as color, or associate words with specific smells or tastes.

When it comes to memory, though, there are plenty of myths floating around. For instance, the claim that left-handed people have better memory capacity than right-handed ones has never been proven. Or that listening to Mozart boosts memory performance – scientists have repeatedly debunked this so-called Mozart effect. One of the most persistent myths is that memory inevitably deteriorates with age. But research shows that in healthy aging, neuron loss is actually minimal. What’s more, new neurons and synapses continue to form even in old age. And like a muscle, the brain grows stronger with training. A senior citizen who actively works on themselves can easily have a better memory than a lazy twenty-year-old.

Brain boosters

If you want your memory to thrive, you should focus on a trio of factors that act like rocket fuel for your brain. First and foremost: mental activity. The more we challenge our brain, the stronger its synaptic plasticity gets. Start learning Swahili, try playing the ukulele, buy a new board game, or brainstorm with friends. Your memory will thank you.

Exercising helps, too. “Physical activity increases blood flow to the brain. It also produces lactate in the muscles, which acts as fuel for neurons,” Stuchlík explains. The third factor is quality sleep – seven to nine hours a night – during which your brain consolidates memories and repairs damaged synapses.

Retention of information doesn’t occur only during sleep, though, but also during rest. That’s why experts recommend studying in short intervals with regular breaks. One effective method is the Pomodoro Technique, named after a tomato-shaped kitchen timer. According to this method, every 25 minutes of focused work should be followed by a 5-minute break – ideal for stretching or exercising a bit. This way, you retain significantly more information.

The effectiveness of the Pomodoro Technique has even been examined at the molecular level.

GAMIFYING MEMORY

Memory can be improved using various techniques. With their help, anyone can cram vast amounts of information into their mind. These following tricks can transform hard-to-remember numbers, names, or vocab words into vivid images that our memory naturally responds to. And the more absurd, ridiculous, or gross these associations are, the better – they pack an emotional punch, which makes memories stick more deeply.

- Let the Story Guide You

A snowman rolls up to an ATM. There, he meets a swan that suddenly slaps handcuffs on him and ties him to a chair – until he melts away. The work of a budding surrealist? Not quite. This kind of bizarre “microstory” can help you remember, for instance, your PIN (in this case, 8234). The human brain is surprisingly good at remembering stories, which is why so many memory techniques make use of them. This one, for example, relies on the visual resemblance of numeral digits to objects.

- Mnemonics & Rhymes

Memory devices can help lock tricky information into your head. Most often, these are acrostics – sentences where each word starts with the same letter as the concept you’re trying to remember (e. g., Please Excuse My Dear Aunt Sally – Parentheses, Exponents, Multiply, Divide, Add, and Subtract; the order of operations for math). Rhymed songs (like the ABCs or “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue…”) also help information recall. - The Mnemonic Major System

This number-memorizing technique was developed in what is now Germany some four hundred years ago. Each digit from one to nine is assigned a consonant that resembles it in some way (1 = T; 2 = N, because it has two “legs”; 3 = M, for its three “legs”). Consonant clusters alone would be hard to remember, so vowels are added as fillers to form syllables to create words. The number 33 becomes “mama,” 99 becomes “papa.” And once you’ve got words, you can build stories – letting you remember practically limitless amounts of numerical data. Memorizing a friend’s phone number becomes a breeze – all you need is to encrypt it into a silly sentence you’ll be able to recall in seconds. - Down Memory Lane

Roman statesman Cicero and other ancient orators would wow crowds with several-hours-long speeches delivered without a single written note. Did philosophers in antiquity just have better memories? Not at all! They had simply mastered the most powerful memory technique of all: the method of loci, also known as the mind palace or memory journey. This mental “hack,” popularized by BBC’s Sherlock Holmes, involves mentally creating a path through a familiar environment, identifying specific points along it, and anchoring the things you want to remember at those points. We’re evolutionarily wired to remember spatial locations incredibly well. Want to memorize a ten-item shopping list? A memory journey through your own body or car will do. Pick your anchor points and assign the items: hang a yogurt on the windshield wiper and imagine it smearing all over the glass; skewer a banana on the antenna… For larger amounts of information, choose a longer route – your commute to school or work, or a mental tour of your apartment. Using this method, you can memorize an hour-long presentation, a hundred vocabulary words, even all the articles of the civil code. All you need is practice!

The article first came out in Czech in the 1/2025 issue of A / Easy:

1/2025 (version for browsing)

1/2025 (version for download)

Written and prepared by: Radka Římanová, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS; Shutterstock; editorial archive

The text and photos labeled CC are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text and photos labeled CC are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- A little-known chapter of history: Czechoslovaks who fought in the Wehrmacht

- Twenty years of EURAXESS: Supporting researchers in motion

- Researching scent: Cleopatra’s legacy, Egyptian rituals, and ancient heritage

- The secret of termites: Long-lived social insects that live in advanced colonies

- Two ERC Synergy Grants awarded to the Czech Academy of Sciences

- Nine CAS researchers received the 2025 Praemium Academiae and Lumina Quaeruntur

- Step inside the world of research: Week of the Czech Academy of Sciences 2025

- A / Magazine: Bugs, the rusting human body, and beauties from the kingdom of ice

- PHOTO STORY: The invasive black bullhead catfish threatens Czech fishponds

- Rewrite the textbooks – we’ve found a bone; aka When science takes a wild turn

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.