When Cars Fly and Bullets Swerve – Physics Gone Wrong on the Silver Screen

03. 02. 2026

Sometimes the abilities of action-movie heroes are enough to make your jaw drop. They can see through walls, shoot around corners, and seem completely immune to gravity. Which movie blunders are guaranteed to make scientists groan? We took a look at some of them with Jan Kaufman from the Institute of Physics of the CAS in the following article, first published in Czech in A / Easy.

*

UP, UP AND AWAY?

Bus no. 2525, full of passengers, is hurtling down the freeway. Sandra Bullock, playing an ordinary civilian who’s ended up behind the wheel, can’t slow down even a little. If she does, a bomb planted on the bus by the deranged, blackmailing bad guy will explode. Inside the speeding vehicle, a very young Keanu Reeves, cast as a police officer, is trying to defuse the situation. Then he hears over the radio that disaster lies ahead. The freeway isn’t completely finished – about fifteen meters of the blacktop are missing. There’s no other option but to try and jump it.

“Everybody hold on!” he shouts, and the driver has no choice but to hit the gas. The passengers pray, the end of the tarmac zooming toward them, and then – whoosh! How does this iconic scene from the two-time Oscar-winning American thriller Speed (1994) play out? To the amazement of scientists everywhere, it works. The bus sails across the gap, lands on the other side, and the driver manages to keep driving. Alas, the bomb keeps ticking.

Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock in the film Speed.

WHAT’S WRONG HERE?

All thrown or flung objects moving through Earth’s gravitational field follow what’s known as a ballistic trajectory – a curved path shaped like a parabola. The moment the bus left the solid blacktop, gravity would immediately pull it downward along such a curve. In the movie, however, the front of the bus magically pitches upward, which makes no sense physics-wise.

The bus could only clear the gap if a ramp or launch platform at just the right angle helped it take off at the end of the completed section of highway. But there’s nothing like that in the scene. Hypothetically, the bus could barely make it across if it accelerated to more than 370 km/h (230 mph), which is, quite simply, technically impossible.

|

DID YOU KNOW? If the plot is engaging enough, viewers and readers can become so absorbed in it that they stop questioning the logic or realism of individual scenes. Filmmakers often rely on this effect, known as suspension of disbelief – the audience’s willingness to set aside their doubts and just go along for the ride. |

*

ENHANCE!

An unknown killer has fled the crime scene. Detectives must sift through endless hours of surveillance footage from nearby CCTV cameras in the hopes of identifying the suspect. “That’s our victim,” one of them says excitedly, pointing at a blurry figure arguing with someone on the screen. “Magnification times one hundred, for starters. Now boost the contrast and sharpness and smooth it out,” his partner urges, watching over his shoulder. Moments later, they’re staring at a crisp, detailed image of the victim. All that’s left is to zoom in again, focus on the reflection in their eye, and “pull out” a perfectly sharp portrait of the murderer. “We’ve got him!” the investigator shouts triumphantly.

Here, Mr. Bean illustrates that the magnification of stills from video footage has its limits.

WHAT’S WRONG HERE?

While TV detectives can reconstruct a crystal-clear portrait of a suspect from a blurry blob, real forensic investigators run up against hard physical limits. Security cameras usually have fairly low resolution and often record only a few frames per second. If you only enlarge such footage, all you get is bigger, blurrier pixels.

It’s true that advanced modern techniques can combine data from multiple frames to create a sharper image with higher resolution, revealing details that weren’t visible to the naked eye in the original video. Even so, they come nowhere near a hundredfold zoom. At best, they might manage a twofold enlargement.

Some filmmakers, however, act as if they have access to infinite image quality. That’s why police procedural shows (such as CSI: Miami or CSI: NY) are full of magical commands such as “Enhance!” as if saying the word alone could conjure detail out of thin air. Take a look yourself.

Movie characters are often shown with words from the screen reflected directly on their faces. For that to happen, they’d have to be staring into a projector, not a screen. This effect is mainly used in action films to liven up otherwise dull shots.

A character watching a missile launch in The Rock (1996).

|

WHAT ABOUT AI? The most advanced AI algorithms can often enlarge and ‘enhance’ images much more dramatically. But any missing details are filled in based on what the system has ‘seen’ during training and what seems most similar,” says Barbara Zitová from the Institute of Information Theory and Automation of the CAS. “The result may look convincing and less grainy, but the AI can easily ‘invent’ features that weren’t there originally. That’s why this method is inadmissible in court – judges need real evidence.” |

*

MISBEHAVING BULLETS

An ordinary guy named Wesley Gibson (James McAvoy) discovers that his father was the head of a secret society of hired killers – and that he’s supposed to take over the family business. It’s up to two mentors, played by Angelina Jolie and Morgan Freeman, to turn him into an assassin. Part of the training involves learning how to change a bullet’s trajectory with nothing more than a flick of the wrist – a skill the protagonist quickly masters thanks to his teachers’ persuasive methods. Managing to curve bullets around the alluring Angelina or even around a dead pig to hit a target behind it is no problem at all in the American action flick Wanted (2008).

WHAT’S WRONG HERE?

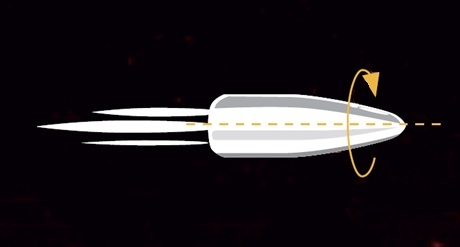

A soccer ball can be kicked so that its trajectory curves in midair thanks to the Magnus effect, but nothing like that is possible with modern firearms. That’s because bullets aren’t spherical, and by their very geometry, a gun barrel can’t put them into a spin around an axis perpendicular to their direction of travel. Bullets are elongated cylinders, so when they leave the barrel, they do spin – thanks to the spiral grooves inside the barrel – but only around their long axis which runs parallel to their flight path. This type of rotation gives them stability and accuracy. Flicking your wrist as you pull the trigger can’t impact a bullet’s trajectory once it has left the barrel. For a projectile’s path to curve, some kind of sideways force would have to act on it. In this film case, there simply isn’t one – and no, love for Angelina Jolie’s character doesn’t count.

The rotation around a bullet’s long axis ensures stability and accuracy.

|

DID YOU KNOW? Bullets lose speed very quickly in water, which can act as an effective shield. Water is much denser than air, so projectiles slow down, deflect, or even break apart upon impact. At a depth of just one meter, a person is already safe from most rifles – and at three meters, they’d almost certainly be out of reach of any firearm. |

*

LET ME GO!

In Gravity (2013), astronauts Ryan Stone and Matt Kowalski, played by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney, lose their space shuttle after it’s struck by orbital debris. Tethered together, they try to reach the International Space Station (ISS) to survive. When they finally get close, they can’t grab hold, and the tether snaps. Stone ends up tangled in ropes attached to the station, but Kowalski keeps drifting away. The young astronaut manages to grab him, but he keeps pulling her with him away from the station. At that moment, Kowalski makes a heroic decision. “You have to let me go, or we both die,” he says calmly, unclipping himself from the tether Stone is clutching in her hand. “Nooo!” she screams as her mentor disappears forever into the blackness of space.

George Clooney in Gravity.

WHAT’S WRONG HERE?

Once they got caught by the ropes attached to the ISS, the motion of both astronauts in weightlessness would have stabilized. According to Newton’s first law, an object remains at rest or moves at a constant velocity in a straight line unless acted upon by an external force.

Thanks to inertia, the pair, connected by a rope, would have remained motionless without any external force acting on them – and there isn’t one here. Kowalski being “pulled away” into the depths of space has no logical explanation. Although Gravity is rightly praised for trying to stick to realistic space physics, in this scene, physics evidently took a back seat to emotional impact.

|

DID YOU KNOW? If space movies were accurate according to physics, they would be nearly silent. That’s because sound doesn’t travel in space. It’s a mechanical wave that needs a medium – gas, liquid, or solid – to propagate. In the vacuum of space, there’s nothing for sound waves to set vibrating. |

*

A HOLLYWOOD-STYLE COLLISION

In Mission: Impossible II (2000), agent Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) chases terrorist Sean Ambrose (Dougray Scott) on a motorcycle. The wild pursuit, full of gunfire and dangerous stunts, climaxes on a dusty coastal road, where the two rivals race toward each other at full speed. They each pop a wheelie, but instead of crashing head-on, they leap from their bikes at just the right moment, colliding with each other midair. This is followed by a shared plunge off a several-meter-high cliff – and after landing on the beach, the final fistfight showdown can begin.

WHAT’S WRONG HERE?

The men were riding toward each other at speeds of around 100 km/h, meaning the relative collision speed was about 200 km/h. In a direct impact, both would have had to come to a stop in a fraction of a second, forcing their bodies to absorb a massive amount of kinetic energy all at once. The collision would subject the two men to extreme g-forces, leading to broken bones, internal bleeding, or even death. On top of that, timing such a midair collision with that level of precision would be practically impossible.

|

DID YOU KNOW? Deadly g-forces during impacts and falls are among the most commonly overlooked physical phenomena in action movies. The Fast & Furious franchise ignores them with particular enthusiasm.

|

*

A PIERCING GAZE

As Agent 007, Pierce Brosnan strolls unobtrusively through the L’Or Noir casino in The World Is Not Enough (1999). Because he needs to figure out which of the guests are armed, he puts on a new gadget from inventor Q: X-ray glasses that look like ordinary, slightly tinted eyewear. Thanks to them, he can instantly see what people are hiding under their clothes – guns, knives, and even lingerie.

WHAT’S WRONG HERE?

X-ray glasses – much like the X-ray targeting weapon that lets Arnold Schwarzenegger see enemies through walls in Eraser (1996) – look cool, but from a physics standpoint, they simply make no sense. Real X-ray imaging requires not only a powerful source of radiation, but also a detector that captures the radiation and converts it into an image. That means that in the Bond movie, every scanned guest would have to be standing in front of an imaging plate. What’s more, X-rays pass through the entire body, so Bond wouldn’t just see weapons and underwear, but also bones and internal organs. And most importantly, the dangerous ionizing radiation would seal Bond’s fate long before he could order his favorite vodka martini.

Pierce Brosnan in The World Is Not Enough (1999).

*

|

Ing. Jan Kaufman, Ph.D.

Jan Kaufman was an exceptionally curious and inquisitive kid who, wherever he went, always had the urge to examine everything. This compulsion to try things out firsthand and understand how they work eventually led him to study physics. Today, Kaufman works at the HiLASE Centre at the Institute of Physics of the CAS, where he leads a research team focused on laser shock peening (LSP). He’s been a big fan of action movies since childhood, but every now and then, the physical inconsistencies pull him right out of the story. He gives talks about these “fails” at schools and public events – and explained some of them to us as well. |

*

This article on physics fails in movies first came out in Czech in the 2/2025 issue of A / Easy:

2/2025 (version for browsing)

2/2025 (version for download)

All Czech and English issues of A / Easy and A / Magazine – the official quarterly of the Czech Academy of Sciences are available online.

We offer free print copies (of the Czech version and the two English issues from 2024 and 2025) to anyone interested – please contact us at predplatne@ssc.cas.cz.

Written and prepared by: Radka Římanová, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS; YouTube; Gemini AI

The text and bio profile photo are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text and bio profile photo are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- The Academy to Boost Excellence and Careers in Research with New Programs

- Could an asteroid hit Earth? The risk is low, but astronomers are keeping watch

- At the nanoscale, gold can be blood red or blue, says Vladimíra Petráková

- The beauty of Antarctic algae: What can diatoms tell us about climate change?

- Moss as a predator? Photogenic Science reveals the beauty and humor in research

- How does the Academy Council plan to strengthen the Academy’s role? Part 2

- How does the Academy Council plan to strengthen the Academy’s role? Part 1

- Ombudsperson Dana Plavcová: We all play a role in creating a safe workplace

- ERC Consolidator Grant heads to the CAS for “wildlife on the move” project

- A little-known chapter of history: Czechoslovaks who fought in the Wehrmacht

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.