Tibet is changing – the Dalai Lama as the highest authority remains, says Jarmila Ptáčková

11. 04. 2022

She has been returning to Tibet regularly for twenty years now, watching the region transform almost beyond recognition. Grasslands with grazing herds of yaks are giving way to housing developments, and Tibetans are becoming Chinese citizens. Many of the relocated herdsmen are frustrated, out of work, and succumbing to alcoholism. “They have become a plaything in the hands of the government, which they completely depend on,” explains Jarmila Ptáčková of the Oriental Institute of the CAS, which is celebrating its centenary this year.

You’ve studied and worked in Berlin, and you’ve considered settling in Tibet or Beijing. But these days, we’d find you in the Šluknov Hook [northern Czech Republic] instead. How did you find yourself there?

The Šluknov region is more a matter of chance. My family and I were looking for a place to live between Berlin and Prague and I wanted my son to attend a Czech school. So the Czech-German border region was a possible choice. When I first saw the vast meadows and pastures there, they greatly reminded me of the Tibetan plains. I could immediately picture a herd of yaks there.

And there is indeed a herd of yaks grazing behind your house. But you took your imagination even further, didn’t you?

On and off, I’ve spent several years in the Tibetan regions. Mostly among pastoral nomads and their herds. I love the endless grassy plains, so I guess I wanted to bring home at least a piece of Tibet and share it with others. After the yaks joined us, we began building a Tibetan stupa.

A stupa is a Buddhist structure that is meant to symbolise peace and tranquillity. How did you manage to build it?

It was no easy feat. I knew exactly what it’s supposed to look like and contain. But in reality, you end up running into unexpected issues. How many steps should it have? What if the bricks don’t align due to their size and what should the interior look like? I’ve consulted with builders and read through instructions. I even consulted the issue with the monk who accompanied the Dalai Lama on his 2006 visit to the Czech Republic. He ended up drawing me a diagram and explaining what was important for the construction of the stupa.

You eventually added a Mongolian yurt, and most notably the Tibetan House, officially called the Centre for Exploring Asian Regions. What is its purpose?

Bringing a piece of Asia into my own home was an idea I had even before I started working at the Oriental Institute. Colleagues helped me expand upon the idea. The Culture and Information Center for Asia allows us to bring our work closer to people, to share our research and findings with them. We host lectures for schools and the general public, and every July, we organise Eastern Tunes, a festival of Asian music and culture. The pizzeria next door, U bílého jaka (The White Yak), offers visitors a taste of Asia.

So you’ve managed to transplant a bit of Asia to your homeland, but still, don’t you miss the real thing? The COVID-19 pandemic has made travelling quite difficult. When was the last time you were in the region?

With the outbreak of the covid crisis in 2020, I came to realise that the only Asia in my reach at that moment was in my backyard. The last time I visited China and Tibet was in 2019. I managed to go to Nepal for a while in 2021, but travelling to China is complicated at the moment.

Are these difficulties with travel caused by the COVID-19 pandemic or the increasingly more restrictive regime of the People’s Republic of China?

It’s interconnected; the covid crisis has come in handy for the regime. The pandemic can be used as an excuse for many things. China completely isolated itself for a while, with the exception of trade, and it’s practically impossible for researchers of my kind to get into the country right now.

How do you get information directly from Tibet if you can’t go there?

It’s not just Tibet; it’s all of China. We all now have to find new ways of accessing information. One can work with social media, archival materials, and online texts, or communicate with locals via email. But it’s not the same. When you’re not on the ground, it’s hard to follow and understand exactly what’s going on. From 2002 to 2019, I visited Tibet every year for a few weeks or months at a time, and even then you could see how the situation in the peripheral regions of China was changing dynamically. Just an absence of half a year was enough for the situation to change completely.

How was life changing in the areas inhabited by Tibetans at that time?

At the beginning of the millennium, there were still no proper roads in Tibet, and many places lacked electricity and network coverage. Today, it’s a whole other story. China’s peripheral regions, including the Tibetan areas, have been subjected to urbanisation, infrastructure development, and population control. Almost overnight, Tibetans have woken up to a whole new era and are struggling to find their place in it. We can read about what’s happened the past two years from official sources like the Xinhua News Agency, but what they present is a very distorted view. A visit in person to verify the facts is therefore absolutely essential, but impossible.

In your articles, you refer to your “informants” on the ground, but you don’t mention names. Is international contact risky for them?

It’s not safe to make their names public. I try to protect my contacts. That’s also why I avoid getting information via email, because any outgoing communication abroad can bring with it sanctions from the government. China is significantly ahead of the curve when it comes to technology and its usefulness in controlling its own people, and the situation keeps getting worse.

Let’s switch focus directly to Tibet. We have the Tibet Autonomous Region, known as TAR, with Lhasa as its capital. However, Tibetans also live elsewhere. Let’s clarify which areas we’re talking about.

The ethno-cultural region of Tibet covers a much larger area than just the Tibet Autonomous Region. It is vast and represents about half the total expanse of historic Tibet. Tibetans also make up the majority of the population in the Chinese province of Qinghai, which lies to the north-east of the autonomous region and is called Ambo. It is the region I specialise in and visit most often. The third cultural and linguistic Tibetan area is the Kham eastern province of Tibet, which has for the most part been administratively incorporated into the Chinese Sichuan province.

When we welcome the Dalai Lama in Europe, we see him as the exiled representative of Tibet. But which part of Tibet does he actually represent?

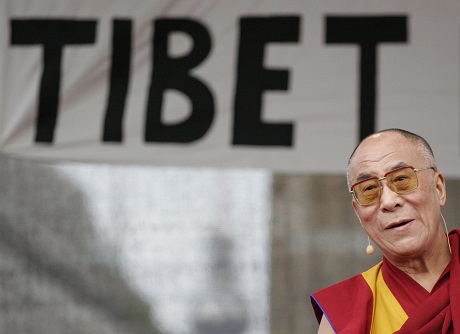

The current Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government-in-exile represent all Tibetans, and for most of them, the Dalai Lama still embodies the ultimate authority, which is, of course, a thorn in the side of the Chinese regime.

The spiritual leader of Tibet, the Dalai Lama

When we say ‘Tibetan’, what springs to mind is typically the image of a monk, a person who draws their wisdom from their spirituality. But what does it really mean to be a Tibetan in the present day?

The Czechs have a certain awareness of Tibet, especially thanks to Václav Havel and his contacts with the Dalai Lama. He was the world’s first head of state to officially welcome the Dalai Lama as a state representative. Us Czechs know roughly where Tibet is located, and that Tibetans live under Chinese rule. However, our notion of ordinary Tibetans is quite distorted. We tend to think that people there live in harmony; in touch with nature and spirituality. But in reality, the ordinary Tibetan is not so different from me and you. They have the same aspirations, wishes to have a comfortable life, money, the latest type of smartphone, and the opportunity to send their children to a good school.

How important is religion to Tibetans today?

In the modern world that the Chinese government has developed in the Tibetan areas over the past twenty years, the way of life has changed significantly. People can now earn money and buy whatever they want. More and more people are employed or are trying to run businesses. Life has sped up and there is less and less time to practice religion. But rather than religion disappearing, it is undergoing a process of modernisation instead. For instance, young entrepreneurs don’t have time to frequent temples or spin a prayer mill at home. Instead, they purchase a solar-powered prayer mill and put it in their car or office.

Here we should explain how such a prayer mill works to better understand.

Picture a cylindrical hand-held prayer mill that is attached to a metal or wooden handle. Inside is a rolled-up piece of paper inscribed with prayers. You pray while spinning it, thus fulfilling your religious duty. Traditionally, you spin the prayer mill by hand, but if you possess the means, why not get a modern, electric prayer mill instead? Even Tibetans are adapting their religious practices to today’s needs.

Traditional prayer mill

In Czechoslovakia under Communist rule, religion was controlled by the regime, which actively discouraged people from practicing their faith. Is it similar in Tibet?

Religious freedom is a problem throughout China, not just in Tibet alone. As part of the fight against anything foreign, the Chinese government is restricting especially Christianity and Islam. With Buddhism, the question is whether you can consider it domestic or foreign influence. There is a great deal of room for interpretation. In any case, Tibetan Buddhism has become the target of a campaign to ethnicize the religion in recent years. Red Chinese flags flutter outside monasteries, slogans and portraits of Xi Jinping hang on the walls. The government is calling on Tibetans to stop making financial donations to monasteries – this, too, is called “fighting poverty” in China.

What power does the current regime have over Tibetan monasteries?

The government has tried to seize control of the monasteries from the very beginning, since the 1950s. However, it had to retain a certain amount of freedom to express religion to maintain peace, and this worked for several decades. Now, it is changing. In recent years, the Chinese government has definitively incorporated the peripheral areas into a functioning infrastructure that allows the regime virtually unlimited oversight and ability to intervene. Thus, the influence of monasteries and other religious institutions, as parallel sources of authority to the centralized government and the Chinese Communist Party, is being deliberately curtailed. The number of monks is being reduced, and monastery abbots are required to undergo patriotic education.

Tibetan is quite different from Standard Chinese (Mandarin), both in writing and pronunciation. Are Tibetans “allowed” to use their own language?

These are two completely different language families. Lhasa Tibetan falls under the Tibeto-Burman languages. Even the script is different. Tibetans do not use Chinese characters for writing, but an alphabet based on Sanskrit. In the autonomous regions, the use of Tibetans’ own language should be guaranteed when it comes to official affairs and education. However, the government is now trying to universally impose classes in schools taught only in Chinese, and even official documents are not always made available in translation. I’ve witnessed, for instance, nomads – who had to relocate from the grasslands to newly built housing developments – being given a contract to sign that was only in Chinese. They had to sign something they didn’t understand at all. But many of them wouldn’t have been able to read the one in Tibetan either; a large part of the older generation cannot read or write.

Nowadays, it’s not easy to just say “I am Tibetan”; it’s the identity of “Chinese citizen” that is promoted. What does this look like in practice?

No minorities have it easy in China. The Chinese citizen comes first; cultural and ethnic traditions are secondary. Theoretically, Chinese citizens should be equal regardless of origin. But unfortunately, this does not translate into reality. The regime requires everyone to declare themselves as Chinese citizens, but ethnicity is still listed on ID cards. And people are treated accordingly.

We’ve mentioned the relocating of Tibetan nomads from the grasslands to housing developments and the construction of infrastructure. Let us add that these changes are in line with the ‘Open Up the West’ strategy that the government announced at the start of the new millennium. What did or does it want to achieve?

What is meant by the West is, in fact, about seventy percent of China’s territory. The East, then, is the coast with metropolises such as Shanghai. Money has been pumped into the East since the 1980s when China began to open up to the world and was in need of foreign investments. Along the coast are ports and airports, and the region soon became the centre of the economy and contact with the world. By the turn of the millennium, you could find modern cities booming there, but inland and further West, it’s as if time stood still. That was the first time I visited the area, and it was apples and oranges. Almost nothing had changed in Tibet from the 1950s to the end of the millennium. Rolling grasslands, nomads with herds of yaks, no infrastructure. In 2004, a journey from a nomadic area to the nearest centre, a hundred kilometres away, could still take up to two days.

So the government decided to open up to the world and modernise Western China as well. How is that coming along?

The East of China was becoming rapidly wealthier and the economic and social disparities between East and West were starting to become unsustainable. Many people migrated from Central and Western China to find work in the East to earn money, where they lived without legal status and as a result, social problems and unrest ensued. The government therefore launched a programme to develop the Western part of the country and started heavily subsidising it. In 2004, when I was in eastern Tibet, the streets in towns and deserted roads in the middle of the plains were flooded with slogans about the great opening up of the West, about how everything was going to be great.

The Chinese government is relocating traditional herders into cities to better exert control over them and extract mineral resources found in the areas.

The proclaimed goal was to catch up with the East. But I’m assuming the intent was not as altruistic as presented by official press sources. What are the other dimensions of the strategy?

To catch up with the standard of living in the East was one thing. At the same time, everything was presented as an intention to lift the population in the West out of its so-called backward way of life. To turn the pastoral herders into urbanites. It was a less publicly mentioned fact that the region was very rich in mineral resources which hadn’t yet been exploited, along with the fact that the West is a sparsely populated, vast area, while the East is overcrowded with tens of millions of people. So the aim was definitely not only to support the population in the West, as was presented officially, but to help the whole of China. In the first phase, the aim was to build infrastructure – roads, railways, airports – and to connect the western peripheral regions to Central China. Once you have decent roads, you can start mining mineral resources, relocating people from the East, developing cities, and exerting more control and influence over the lives of the local inhabitants. And that’s what happened.

One of the phases was the abolishment of pastures and housing development. The Communist Chinese government claimed to be helping the locals, lifting them out of poverty. Is it possible to say how voluntary these relocations were?

The reasons most often given by the government for sedentarisation, i.e., the relocation into housing developments, are about improving the living conditions of the herders and protecting the environment, which is supposedly under long-term threat from livestock grazing. However, the government is subjecting the cleared land to construction and mining. In addition, relocating people into newly built housing greatly improved population control, which became a priority after the 2008 riots. When it comes to relocation efforts, the locals haven’t had much choice. While it was all seemingly voluntary, they were given minimal time to decide. Officials would tell them, for instance, that they had a great opportunity to move into a house for free or for a very low fee, and they would have access to education and health care. But they had to make a decision within the week or lose the opportunity. Those who refused to move were sometimes threatened with sanctions. As a result, Tibetan nomads relocated in rather massive numbers.

Two decades have passed since this strategy was launched. Do we even know how the former pastoral nomads are faring in the cities today?

The housing developments are mostly located on the outskirts of district cities or towns. But some of them are completely out of the way, in the middle of pastures. A lot of things have been left unfinished. Where will all the former herders work? What will they do for a living? Even several years after the construction being finished, many housing developments have no electricity or water supply. Those who could returned to the pastures. Those who relinquished their right to the government to use the pastures or sold their herds haven’t been able to do so. Many of these people feel great frustration. They have no means to make a living and are just waiting for welfare. They’ve become a plaything in the hands of a government on which they are now totally dependent. Alcoholism and other problems are on the rise.

By the end of 2020, the People’s Republic of China had set itself the goal of eliminating poverty. How has such an ambitious plan worked out?

In early 2021, China announced with fanfare that it had completely eliminated poverty. And yes, on paper, it has indeed been eliminated. It all boils down to how you define poverty, where its boundaries are drawn. In Tibetan areas, the government includes social welfare in the income of the population, so in terms of income, the poverty line isn’t necessarily crossed. But this says nothing about the stability and sustainability of living standards.

In recent years, the situation of the Uighurs, a large Turkic minority living in China’s western province of Xinjiang, has often been mentioned. For example, information has leaked out about internment re-education camps. Do similar detention camps exist for Tibetans?

There are no re-education camps on such a massive scale as those in Xinjiang, but we would certainly find parallels in Tibet. It was Tibet which used to be considered problematic. Already in the 1950s, it was common for inconvenient people to suddenly disappear and the population to be under permanent control. Everything got worse after 2008, in the wake of the Summer Olympics in Beijing. Tibetans wanted to take advantage of the whole world watching China and decided to draw attention to their situation. The reaction of the Chinese government was drastic.

Chinese soldiers in Lhasa, Tibet

The protests started in March 2008 in Lhasa to mark the anniversary of the Dalai Lama’s departure into exile, and unrest broke out in other Tibetan areas. The Chinese authorities responded with a brutal crackdown, with reports of hundreds of casualties (deaths) and thousands of arrests.

In 2008, there were fewer Chinese military bases in Tibetan areas than there are today. It was the roads, railways, and airports, i.e., the infrastructure that the Chinese government ‘gifted’ to the Tibetan people, which enabled the rapid relocation of troops to the problematic areas. Between March (when the riots broke out) and August (when the Olympics began), trucks with soldiers armed to the teeth would patrol the streets every day. Many people ended up in jail during that time, including many popular artists, some for being found with a picture of the Tibetan flag or for singing Tibetan songs. The situation didn’t ease up even after the Olympics. The soldiers remained in Tibet and security checks intensified. All of this was exacerbated by COVID-19, too. Population monitoring is ubiquitous across the whole of China.

So governmental control over the population is similar both in Tibet and Xinjiang, and there is little to speak of in terms of freedom of movement?

Governor Chen Quanguo, who imposed strict measures on Tibetans after the Olympics, was transferred to Xinjiang in 2016. There, he put to use what had worked in Tibet, such as thoroughly monitoring people’s movement through ubiquitous camera surveillance and checkpoints. Any sort of mobility in China is unwelcome and suspect, as it increases one’s social circles. China uses a system of classifying the population; you fall into different categories according to the number of social points you gain. Some citizens earn the right to hold a passport, while others can’t even buy a bus ticket.

The last Olympics sparked a wave of solidarity with the Tibetans around the world, with calls for a boycott of the sports event. Just fourteen years later, we found ourselves in the same situation again, as the Winter Olympics were held in Beijing in 2022. Does this mean that the world is quietly tolerating the violation of human rights in China?

It is a surprise that China was able to qualify again. Beijing is the first city in the world to ever have hosted two Olympic Games, summer and winter. Why the International Olympic Committee chose China in 2008 is understandable. At the time, the country seemed to be changing and opening up; the world probably assumed that the Olympics would encourage development in that direction. Unfortunately, the opposite was true. China more or less perceives being chosen as the host of the Olympics again as an endorsement of its policies.

Jarmila Ptáčková. (CC)

Dr. Phil. Jarmila Ptáčková

The Oriental Institute of the CAS

She completed her studies in Sinology and Tibetology at the Humboldt University in Berlin. She has been working at the Oriental Institute of the CAS since 2014 as a researcher at the Department of East Asia. She is co-investigator of a project (supported by the Lumina quaeruntur fellowship of the CAS) on the context of national and foreign policy in present-day China. Along with Ondřej Klimeš and in collaboration with universities in Warsaw, Leipzig, and Dublin, Ptáčková has applied for an ERC (European Research Council) Synergy grant concerning a follow-up research focus.

Prepared by: Leona Matušková, Division of External Relations, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, Division of External Relations, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, Division of External Relations, CAO of the CAS; Shutterstock

Texts and photographs labelled (CC) are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Texts and photographs labelled (CC) are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- How does the Academy Council plan to strengthen the Academy’s role? Part 2

- How does the Academy Council plan to strengthen the Academy’s role? Part 1

- Ombudsperson Dana Plavcová: We all play a role in creating a safe workplace

- ERC Consolidator Grant heads to the CAS for “wildlife on the move” project

- A little-known chapter of history: Czechoslovaks who fought in the Wehrmacht

- Twenty years of EURAXESS: Supporting researchers in motion

- Researching scent: Cleopatra’s legacy, Egyptian rituals, and ancient heritage

- The secret of termites: Long-lived social insects that live in advanced colonies

- Two ERC Synergy Grants awarded to the Czech Academy of Sciences

- Nine CAS researchers received the 2025 Praemium Academiae and Lumina Quaeruntur

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.