The ABCs of writing: Why did its invention mark a turning point for humankind?

30. 05. 2025

Our thoughts are fleeting, up in the air, hard to pin down. But once something is written down, it’s set in stone. Our ancestors understood this, which is why they came up with various ways to record what mattered most. It’s estimated that roughly 400 different writing systems exist. How did their invention shape the development of society as a whole, and what do we use writing for today? We explored its history and looked into a few fun facts in the latest issue of A / Easy magazine.

You’re reading this text in the Latin alphabet – the most widely used writing system in the world. But could you read it in the Cyrillic script? While their modern forms differ, they do share something in common: history. Writing allows us to capture spoken language – everything I say can also be written down. It began developing in the third millennium BCE as a tool for administering increasingly complex human societies – in Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, and China – and at that time, knowledge of writing was limited to a small number of individuals.

“What really matters for our [Czech] region, though, is the emergence of the Phoenician alphabet, which drew on Egyptian hieroglyphs and cuneiform script. It reached ancient Greece via the Phoenicians, where it was adapted for Greek use. From there, it spread to the Etruscans and then to ancient Rome, where it underwent further modification,” explains historian Petr Sedláček from the Institute of History of the Czech Academy of Sciences (CAS). This historical development gave rise to the distinction between the Latin alphabet, from which Western scripts are derived, and the Greek alphabet, from which Cyrillic later developed.

Ancient cuneiform script from the Fortress of Van, ninth–sixth centuries BCE.

Knotted but not tangled

How long have people been recording what matters to them? And how did they do it in times before writing as we know it today even existed? Since humans are ingenious creatures, they came up with all sorts of ways. “The oldest systems date back to between the fifteenth and tenth millennia BCE, when the first precursors of writing appeared – specific symbols used mainly to denote ownership or to keep track of loans,” Sedláček says, adding that they also served ritual purposes or functioned as ownership marks. During the Upper Paleolithic, such symbols were used by, for instance, Arabs, the Sámi, or the Mari people. These systems of signs, however, typically remained confined to the communities where they originated.

A much younger example is the knotted-cord writing system known as quipu (or khipu). The Inca literally wove information into colored cords using knots of various shapes. In Ireland, the Celts used ogham, or the “Celtic tree alphabet,” carving inscriptions into wood or stone.

When paper conquered the world

Nowadays, we either jot things down on paper or record information electronically – tapping it out on a keyboard and reading it on a screen. But in the past, people wrote on all sorts of materials.

“In antiquity, the most common writing medium was papyrus. It was relatively cheap to produce but brittle and quick to deteriorate,” Sedláček explains. In the Middle Ages, people mainly wrote on parchment. Made from animal hides, it was known for its high quality and durability.

The papyrus plant (Cyperus papyrus) was used to produce the writing material of the same name.

But parchment was extremely expensive and labor-intensive to produce, which is why it ultimately couldn’t compete with paper – a much cheaper alternative, even though it was originally considered an inferior and less durable material. “Paper originated in ancient China and made its way to Europe via the Arab world. Following the invention of the printing press [around 1440], paper became the dominant writing material, while parchment survived longest in use at the papal chancery,” the historian adds.

The legacy of Saint Cyril – still many unknowns

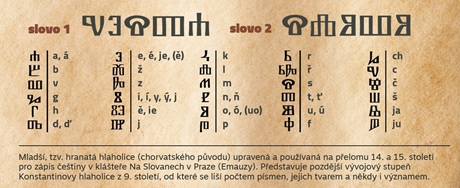

The Byzantine scholar Constantine, who later took the monastic name Cyril, went down in history as the creator of the Glagolitic script – the oldest known Slavic alphabet – which he devised for his mission to Great Moravia. It was originally simply called the Slavic script, and its modern name derives from the Old Church Slavonic verb glagoljati (to speak, or to say Mass).

To this day, researchers continue to debate many questions surrounding the origins of Glagolitic: What writing systems was Constantine familiar with, and which might he have drawn on to create this new script? What Christian symbolism and geometric principles did he encode in its design? What did “Glagolitic 1.0” look like – how many letters did the earliest version contain, and what did they signify?

According to Vladislav Knoll from the Institute of Slavonic Studies of the CAS, there is still speculation around things like the existence of three distinct “i” and two different “ch” and “f” letters, and the use of two letters to write the “y” sound. Among the first generations of scribes, the rules for how to use individual letters were evidently not set yet. Some letters, in fact, are known only from the oldest alphabet lists, known as abecedaries.

Can you decode these words in Glagolitic?

How to understand each other without words

Colon – dash – parenthesis. And just like that, the first emoticon was born. The year was 1982, and U.S. computer scientist Scott Fahlman came up with a simple smiley face to distinguish serious messages from jokes on a university message board.

Emoticons, or emojis, are an internationally recognized symbolic script that nearly anyone should be able to understand, since they convey moods and emotions. Could they one day make the leap from informal to formal language? “They’re not words, just symbols and combinations of characters. They definitely have a place in text messages, personal emails, or on social media – in other words, in short and informal texts,” says Markéta Pravdová from the Czech Language Institute of the CAS.

But even within a single culture, one smiley can have more than one meaning. “That’s why these ‘globalisms’ don’t really belong in formal texts, and I don’t expect that to change anytime soon. Just imagine emoticons in the text of a constitution or a law!” the researcher adds.

Don’t play with your food! . . . Well, maybe just a little?

Waiter, there’s a “fly” in my soup! But no worries – I can just scoop it up with a spoon and eat it. It’s actually just a word made out of pasta shaped like letters. Alphabet pasta, also known as alfabeto or alphabetti spaghetti, most likely originated in Italy or France. It began appearing in cookbooks in the late 19th century, when it became especially popular in soups and children’s meals. Alphabet pasta was one of the first “educational” foods – kids could play while learning their ABCs.

Alphabet soup.

From Europe, it quickly spread across the ocean, especially to the United States. Alphabet soup became popular not just there, but also in the Czech lands. It’s hard to say who first started producing letter-shaped pasta there, or when – but it was likely the Zátka brothers, who founded a pasta factory in 1884 in Boršov nad Vltavou, South Bohemia. Today, the two most popular recipes are tomato soup and broth.

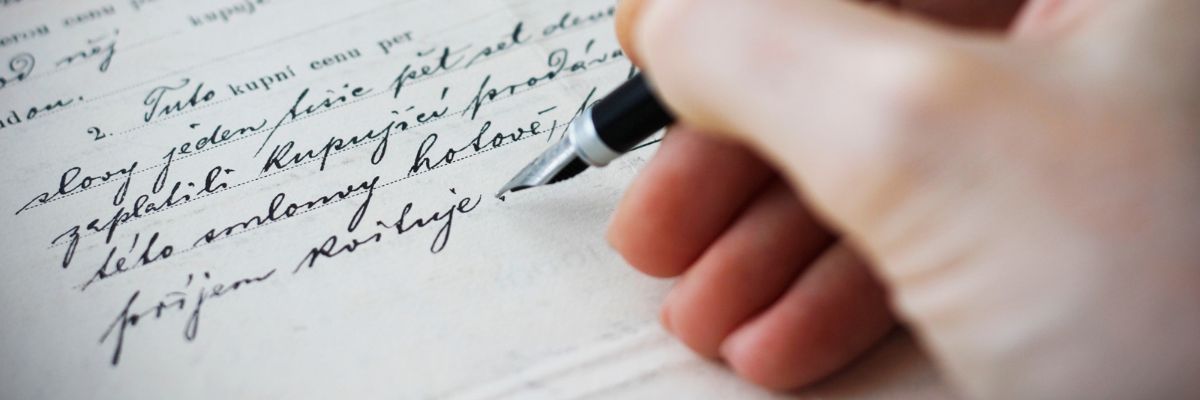

Handwriting – a window into the soul

Is graphology a science – or pseudoscience? Those who practice it believe that a person’s handwriting reflects key traits of their personality. In theory, a graphologist should be able to determine whether the writer is an introvert or extrovert, emotionally or rationally inclined, what temperament they have, and even how they relate to themselves and others.

This approach to understanding people through their handwriting is sometimes confused with forensic handwriting examination. But the two are quite different. The latter is a forensic discipline used in criminal investigations and legal proceedings. It examines and verifies the authorship of texts or signatures and confirms or disproves the identity of the writer. Is that autograph from a famous actor or singer genuine? Did an A-lister football player really sign that ball? An experienced handwriting expert should be able to crack the case.

*

The article first came out in Czech in the 1/2025 issue of A / Easy magazine published by the CAS:

1/2025 (version for browsing)

1/2025 (version for download)

Written and prepared by: Markéta Wernerová, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Shutterstock, editorial archive

The text is released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text is released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- A little-known chapter of history: Czechoslovaks who fought in the Wehrmacht

- Twenty years of EURAXESS: Supporting researchers in motion

- Researching scent: Cleopatra’s legacy, Egyptian rituals, and ancient heritage

- The secret of termites: Long-lived social insects that live in advanced colonies

- Two ERC Synergy Grants awarded to the Czech Academy of Sciences

- Nine CAS researchers received the 2025 Praemium Academiae and Lumina Quaeruntur

- Step inside the world of research: Week of the Czech Academy of Sciences 2025

- A / Magazine: Bugs, the rusting human body, and beauties from the kingdom of ice

- PHOTO STORY: The invasive black bullhead catfish threatens Czech fishponds

- Rewrite the textbooks – we’ve found a bone; aka When science takes a wild turn

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.