Fun can be had even in the molecular biology of cancer dept, researcher says

05. 01. 2024

Her entire scientific career revolves around cancer. In an ironic twist of fate, the diagnosis recently came into Veronika Vymetálková’s private life as well. But it certainly didn’t wipe the smile off her face or take the wind out of her research sails – quite the opposite! The interview with the researcher from the Institute of Experimental Medicine of the CAS was published in the A / Magazine.

*

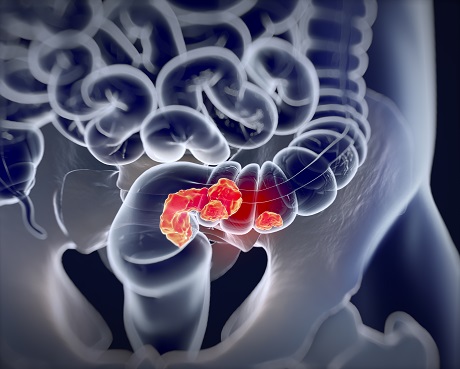

A typical Czech tumour. That’s what we could call colon cancer carcinomas, which is what you focus on. Why has this particular disease until very recently thrived so much in the Czech Republic?

Genetics plays a role in all types of cancer. However, an individual’s lifestyle and diet also have a significant impact on the development of colorectal cancer, as the disease in question is properly called. The fact that just a few years ago, the Czechs were in the top five worldwide in terms of the prevalence and mortality of this diagnosis, may have been partly due to the traditional national cuisine. The ubiquitous beef tenderloin with double cream sauce [svíčková] or the roast pork–dumpling–sauerkraut triad [vepřo knedlo zelo] with beer are, simply put, not good for your gut. I don’t want to throw too much shade at these delicacies, I myself like these dishes, but they likely had an impact on the statistics.

We continue to stuff ourselves with red meat, but fortunately, the Czechs have already left the global top rankings of the incidence of this disease. Why is that?

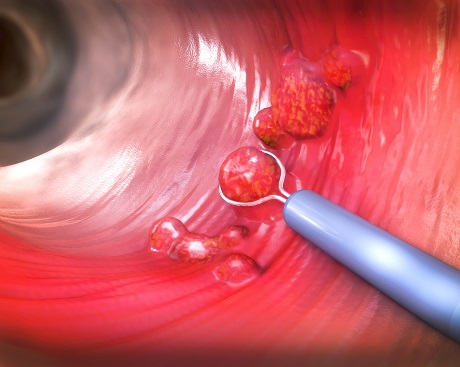

The expansion of prevention has certainly helped. Insurance companies pay for screening tests for people over 50, and these timely screenings can be instrumental in putting a stop to colorectal cancer (CRC). It’s polyps (fleshy growths) that usually gradually give rise to colorectal tumours. So when a patient comes in for a preventive colonoscopy and the doctor discovers a polyp, it can be removed immediately during the examination itself.

So that way, cancer doesn’t even get a chance?

Exactly – basically, the tumour has nothing to grow out of. In recent years, thanks to colorectal cancer screenings, the Czechs have fallen to seventeenth place in the global statistics of CRC incidence. Just FYI, among European countries, colon cancer is currently most prevalent in Hungary, with my native Slovakia close on its heels. Despite the fact that roughly the same percentage of people participate in screening tests in that country as in the Czech Republic. For reasons unknown, prevention there hasn’t worked as well as here.

You mentioned your Slovak origin, but you can pronounce the notoriously difficult Czech “ř” [rʒ] better than a lot of Czech native speakers.

Thank you! I’ve excelled at it due in large part to my children. They both struggled with learning to pronounce it, and since I took them regularly to speech therapy, we all practiced it together for so long that I managed to nail it! I have to give my kids generally a lot of credit for my Czech. When I came to the Czech Republic in 2005 to study for my PhD, I spoke only Slovak. Eventually I married a Czech and stayed in the country. But I didn’t start to improve my Czech until after the birth of my children – to be able to speak the language correctly when talking to them. Today, many people don’t even know I’m not a native speaker of Czech.

In which part of Slovakia did you grow up?

Right in Bratislava, in one of the biggest residential complexes [a mass of ‘communist-style’ concrete blocks, aka paneláky] in Central Europe called Petržalka. At the time of my childhood and adolescence, it didn’t have a very good reputation, but I didn’t really find out about that until later. I have only the best memories. I used to run around outside all the time with my friends, go swimming at Lake Draždiak, which was right there outside my window. And I was always digging holes somewhere.

Why? Did you particularly enjoy digging in the dirt?

Not really, but my dream at that time was to be an archaeologist and I kept hoping I’d find treasure! So I dug and I dug… (laughter). But around the age of ten, I discovered experiments. My dad was an electrician and, one day at work, he got hold of some glass test tubes. I immediately confiscated them and started to experiment with them in secret. In the bathroom, I would mix salt with vinegar, paprika, and water colours and would wait anxiously to see what it would do.

Pretty decent preparation for the real thing!

I had a blast. Later, I still flirted with the idea of going to medical school because I was fascinated by the human body. But the pipetting and the lab won out in the end. I’m not a particularly eloquent person, and it would have been hard for me to get used to interacting with patients on a daily basis. I much prefer to conduct research behind the scenes.

Until recently, the Czechs were in the top five worldwide in the incidence of colorectal cancer.

In the end, cancer research won out. Not exactly a happy subject...

I got into it while I was studying biochemistry. So my journey led me to molecular genetics and biology, and I have no regrets. In many ways, cancer research is still an unexplored field, it’s very dynamic, and you are constantly learning new things. I enjoy the mystery and variables that surround it.

However, your work probably doesn’t offer many opportunities to laugh, does it?

You’d be surprised! We have a great team, and our boss loves dark humour. So fun is to be had even in the molecular biology of cancer department.

Let’s get back to your subject of research. I heard that colorectal cancer is one of the few diseases where race and gender do actually play a role. Is it really ‘biased’ in this way?

It’s true that in general, colon cancer most commonly affects Black and African American populations, even at younger ages. Some studies say this is due to lower levels of physical activity, others say it is due to higher rates of obesity or poorer access to prevention. In contrast, the Jewish population, for instance, is almost free of colorectal cancer.

And what role does gender play?

Although rectal cancer is more common in men, the incidence of colorectal carcinomas is more or less the same regardless of biological sex. However, differences are noticeable in Asia. In fact, Asian women are much less affected by CRC than Asian men. Opinions vary as to why this is so. For example, one earlier study has suggested the protective effect of sex hormones estrogen and progesterone against CRC in postmenopausal women.

You’ve suggested that the traditional Czech cuisine is not great for the gut. What should a person steer clear of if they don’t want to end up with a CRC diagnosis?

Mainly smoking, prefabricated food [ready-to-eat meals], alcohol, high-fat meat dishes... But the risk of developing CRC is also increased by stress, sedentary work, and a lack of vegetables, fruit, and dairy products in our diet... Lifestyle plays a crucial role in this disease. Only fifteen percent of patients have the hereditary form of CRC. The rest of the cases consist of the so-called sporadic form of CRC, which develops on the basis of other factors.

So usually it’s people’s own fault?

It sounds harsh, but basically, yes. That’s probably why colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide. However, in the sad world of cancer, CRC is actually one of the better diagnoses – kind of the lesser of two evils. In fact, if caught early, it is quite treatable, unlike other types of cancer. If doctors detect it in the first stage, they can usually just remove the polyp or tumour surgically. About ninety percent of people survive the next five years after the procedure. Unfortunately, in most cases, CRC is not discovered until a much more advanced stage of the disease, in which case the prognosis is very unfavourable.

The disease also has a lot to do with age, doesn’t it?

Yes, it is more common in older people, but this is true for most types of cancer in general. That's why CRC screenings are recommended to people aged 50 and up. However, in recent years, the percentage of CRC in younger people in their 40s has been increasing. Moreover, it is usually caught at a worse, more advanced stage and is more aggressive. The question is why. According to one theory, it has something to do with the previous presence of an inflammatory disease, such as ulcerative colitis, in the patient’s colon.

The most common chemotherapy drug that doctors prescribe to patients in the more advanced stage of CRC is called 5-fluorouracil. But it’s not exactly a panacea, is it?

Unfortunately, no. As is the case for other types of chemotherapy. In fact, a large proportion of CRC patients develop what is called chemoresistance – they simply stop responding to treatment. It can be congenital, but it can also develop during the course of treatment. Either way, it is one of the main reasons for treatment failure – the recurrence rate for such patients is relatively high soon after treatment.

Can we call this a simple stroke of bad luck, or why is it that the chemo doesn’t work on them?

That’s exactly what I’ve been wondering. In the beginning, I was researching CRC mutations, and it really struck me how common these resistances and associated recurrences are. But why chemotherapy works for some patients and not for others, scientists haven’t been able to find out yet. So I figured I’d try to get to the bottom of it.

Any luck?

We’re on the right track. We’re trying to detect indicators in the patients’ blood that could predict that they’re the ones who will end up with the short end of the stick, so to speak. I specifically target circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) and microRNA (ctRNA). I compare the blood levels of these markers in patients for whom the treatment is working with those individuals for whom the chemotherapy is not working.

Circulating tumour DNA. Judging by the name, it doesn’t seem to be a good sign.

You’re right. Cancer is caused by mutations in our DNA that shouldn’t be there. The mutations cause the cell to turn cancerous and start dividing uncontrollably. Most solid malignant tumours shed this circulating tumour DNA into the bloodstream. During the course of the disease, we are able to track ctDNA in the patient’s blood due to the presence of these mutations.

Colon tumours usually form gradually out of so-called polyps.

What does it look like?

To simplify greatly, I would describe it as a miniature ladder with a single-coloured rung that is floating around in the bloodstream. The rung represents the mutation that doesn’t belong there. Ideally, after chemotherapy, that DNA should no longer be present in the body. But what we have found is that in some chemo-resistant individuals, ctDNA levels continue to rise even after the treatment is concluded.

Does that mean the disease is coming back?

It’s very likely that they have a new tumour forming somewhere or that they have residual cancer cells in their body. We have also found that miRNA levels are quite low in the blood of patients who do not respond well to chemotherapy compared to the blood of healthy individuals. So these two indicators look very promising so far – they could help identify cases with an increased risk of cancer recurrence. Doctors would then be able to monitor these patients more frequently and intercept any possible recurrence of CRC early, for example by giving them stronger treatment. For now, however, this is still just the music of the future.

How much of a distant or not-too-distant future are we talking about?

It’s hard to say. We’re in the laboratory research phase. We still need to test the results on a larger number of patients. Each individual reacts a little differently, so our conclusions will certainly not be applicable to everyone. That is why we also need to identify the specific group of patients for whom our findings are most relevant. So far, this seems to be the case for patients with colorectal cancer. In those we detected ctDNA and lower miRNA levels following treatment, most of them had recurrence of the cancer.

What remains to be explained is what microRNA is.

They’re small non-coding RNA molecules that look like two interwoven combs. If all is going well, they separate from each other and one of them latches onto our long mRNA, which regulates protein and enzyme production. But when something is wrong in the body, either significantly more or fewer of these molecules are produced. And this leads to either a halt in the process of producing the enzymes and proteins needed by the body, or, conversely, an overproduction of those that are useless to us but important to the tumour. Imagine that each of these combs is a different colour and what we are looking for is one specific one that is responsible for the change in protein production.

So you’re on the hunt for special mini ladders and combs in the bloodstream. But how?

We isolate them from blood plasma using commercially available kits. We take a filter, placing plasma on it, and add various liquid substances to it. We wash it out in certain ways, sometimes we siphon off, centrifuge, or add something… We play around with it until what remains on the membrane is exactly what we want – in this case, a mixture of all the ctDNA or microRNA. But in order to find that ladder with that single-coloured rung or that comb of a particular shade, we still have to add specific chemicals, using them to “sift” our way to our goal. It is actually a rather complex, sophisticated, and multi-step process.

Veronika Vymetálková's lab equipment.

How much time does it take?

About two hours of intensive work. Usually, we isolate samples from several donors at once, so we spend about a week on just “sifting” through it from morning into the night. We then analyse the results and compare them statistically. This means that we look for differences and points of contact between patients for whom the treatment works and those for whom it does not.

Sounds like a lot of toiling work.

Yes, but in the early days, when we didn’t know exactly what we were looking for yet, it was much more of a chore – like looking for a needle in a haystack. We were working with the full range of all the microRNAs known so far, looking for the ones whose levels differed most between the groups being compared.

Do hospitals supply you with the needed blood?

Yes, they always call us when they have a fresh supply of blood, our lab technician then comes to collect the material, isolates the plasma from the blood, and freezes it at our institute. Once more blood samples accumulate, we can get to work. The research, however, is very time-consuming, because we need blood from the same individuals from different periods – at the time of diagnosis, just after the end of chemotherapy, and one year after. And these last samples are usually hard to obtain.

I’m guessing that the last thing on people’s minds is donating blood for follow-up testing after they’ve gone through treatment, right?

Exactly. They just want to be healthy. Which, given that I’ve gone through the experience of having cancer myself, I completely empathise with...

With the type you’re currently researching?

No, breast cancer. An unexpected surprise for my 40th birthday, as I got it exactly one year ago. And I have to say, it was a real shock. Before that, I had been coming in for regular check-ups with a lump that had been fine for a long time. But all of a sudden, it started to grow and suddenly it was a tumour at a pretty advanced stage. That’s the type of news nobody wants to hear, no matter if you’re a scientist who’s been studying cancer all your life or anyone else.

How did you come to terms with the diagnosis?

Of course, I was taken aback, and there were tears. But I didn’t let it knock the wind out of my sails. As I was lying in bed at night the day I found out about my illness, I said to myself: okay, maybe I’m going to die. So I prepared letters for my children, chose the music for the funeral, and that brought me closure on the subject of death, as far as I’m concerned. I don’t go back to it anymore. That inner reconciliation was a great comfort to me. And then I started to fight.

You know the A to Zs of cancer. Did your knowledge of the subject make those first personal moments any easier, or is it in this case more of a burden to actually know more?

Even if you have studied everything there is to know about cancer, the reality and personal experience is of course different. I guess it might sound strange, but at one point I said to myself: at least I will find out firsthand how things really work in the body during the illness. My scientist brain kicked in, which probably also helped me cope with the situation better.

Apparently, professional bias can be beneficial sometimes.

Exactly. I also asked the doctors if they needed blood samples from me for any studies. One thing I haven’t done since then is follow breast cancer statistics, which is a bit silly for a researcher. I know from my experience that treatment affects each person differently. So I don’t want to search for myself in any charts. I’m going my own way and just choosing to close my eyes to the statistics at the moment.

And you didn’t go through the “why me” phase at any point?

No, I didn’t feel any sort of self-pity or anger. I saw it as a challenge. I got really motivated, mainly because of my kids and family. I wasn’t afraid of any procedure, chemotherapy, hair loss, radiation or hormonal therapy. On the contrary, I was always ready for the next step – because I knew it would move me closer towards recovery. Even after my breast surgery, I immediately consulted with the doctors whether it would be necessary to remove the other breast as well. And if I ever felt blue, I immediately told myself: I’m doing this and I’m gonna make it.

Have you always been so strong and positive?

Not at all, all my life I’ve been more of a realist or pessimist. A typical stressed-out workaholic who always feels like there’s so little time and so much to do and can’t keep up with it all. I think I may have given myself cancer by being so stressed out about every little thing. Clearly, I needed to hit rock bottom to reevaluate my approach to life. The disease has changed me a lot.

In what way?

I don’t get anxious when I’m running a few minutes late or when my research paper gets rejected. It’s not the end of the world. I don’t care if my house isn’t perfectly clean. Instead of scouring and scrubbing away, I chat with my kids. I just enjoy my days now much more. And I laugh a lot more, in fact, I never used to laugh as much as I do these days. Dark humour has also helped me to get through my treatment. It became very much a part of our household.

Did you undergo laughter therapy?

Basically, yes. It kept us from getting disconcerted, even when difficult situations arose. We laughed when my husband cut my long blond hair at my request a week after I started chemo. And when he took the rest of it off with an electric razor soon after. We just made fun of it. Of everything. One time, I got sick after chemo and ended up hugging the toilet bowl. My husband came to check on me and asked if I wanted him to hold my hair.

Pretty dark humour right there...

Right? But it made me laugh at that moment with my head in the bowl. I just couldn’t take it any other way than as humour. Without humour, you’re bound to get caught up in it all, and that takes away the strength you need to heal and get better.

How long did your treatment last?

For the first six months, my husband drove me to my chemotherapy sessions. At the beginning, I was undergoing the stronger variation, the type that makes your hair fall out. But I avoided that by cutting off my hair early. I’ve hidden the ponytail of my hair and I’m going to keep it until I grow out my hair into the mane I used to have. By the way, this chemotherapy drug is called “The Red Devil”. It’s a deep orange liquid that looks remarkably like Aperol liqueur. I haven’t been able to see or touch that drink since (laughter) !

No wonder!

The Red Devil enters the body through a subcutaneous port [catheter]. After that there was a period of gentler chemotherapy, which is much more frequent. Five weeks after the chemo, I had breast surgery. Finally, three months after that procedure, I underwent a month and a half of radiation therapy.

What about your children? How did they react to all this?

Bravely. But it was not easy for me to tell them about my diagnosis. We had a very recent and rather unpleasant experience with this disease in our family. I was upfront about it with my then 11-year-old daughter and outlined all the possible scenarios. I let my three years younger son know about it in increments. Throughout the therapy, they both respected the fact that mommy needed to rest. My husband rearranged his work schedule and took care of them and the household during that time. He was really, incredibly supportive. It brought us very close together as a family.

You successfully completed your treatment and went straight back to work, i.e., cancer research. Did you feel like changing your focus once you got back into it again?

On the contrary, I’m even more motivated to do research. My own personal experience with cancer has only reassured me that my work is meaningful. If our results are validated and, in the future, will help someone detect the recurrence of CRC in time, I will be the happiest person in the world.

You weren’t tempted to switch focus straight to breast cancer?

No, I feel that would be too personal for me. Part of my scientific work involves evaluating manuscripts submitted by other researchers to various journals for review. I have to confess that I now have to reject those that focus on breast cancer. For a person in remission, i.e., being freshly relieved of symptoms of the disease, it would be quite a challenge I think. I’d be missing the distance I need.

Do you ever manage to get a break from this heavy topic?

Don’t worry! Fortunately, I’ve learned to take it easier than I used to. I know I have to go easy on myself. Because if I overdo it, my body lets itself be known. So if I ever feel like I’m getting tense or feeling on edge, I take a break. I used to ignore it, but I’ve learned to relax in bed with a book.

Not a scientific one, I hope!

Nope! I read mostly historical literature, biographies of rulers, and novels by Czech authors. I love to read! But I can also switch off while weeding our garden and trimming the trees. My husband claims I’m a complete fanatic about the latter – as I’m always taking my pruning shears to this or that plant. It’s just my thing, I guess.

A pointed hobby...

I find snipping and pruning the ultimate relaxation. I used to relax mainly by jogging and exercising, which I unfortunately can’t do at the moment. But I definitely don’t feel sorry for myself. The disease has given me much more than it has taken away. I’ve gained perspective, re-prioritized... And I haven’t let it paralyze me. In short: I got cancer, but cancer never got me!

Ing. Veronika Vymetálková, Ph.D.

INSTITUTE OF EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE OF THE CZECH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Vymetálková graduated from the Faculty of Chemical and Food Technology of the Slovak Technical University in Bratislava. She completed her doctoral studies in molecular biology and genetics at the Third Faculty of Medicine, Charles University in Prague. Since 2005, she has been working at the Institute of Experimental Medicine of the CAS, where she is currently serving as deputy head of the Molecular Biology of Cancer research department. In 2021, she was awarded the [Czech] Minister of Health Award for Medical Research and Development and the Award of the Czech Academy of Sciences for Outstanding Achievement in Research, Experimental Development, and Innovation. In 2023, she received the L’Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Award.

The interview was first published in Czech in the A / Magazine, published by the Czech Academy of Sciences. Free issues of the magazine in Czech are available to anyone interested. You can contact us at predplatne@ssc.cas.cz.

3/2023 (version for browsing)

3/2023 (version for download)

Prepared by: Radka Římanová, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS; Shutterstock

The text and photographs (apart from the image of the intestines) are released for use under the Creative Commons licence.

The text and photographs (apart from the image of the intestines) are released for use under the Creative Commons licence.

Read also

- A trapped state: The pandemic impact on public attitudes, trust, and behavior

- Aerial archaeology: Tracing the footsteps of our ancestors from the sky

- Archaeologists uncover ancient finds along Prague Ring Road

- Our microbiome largely depends on what we eat, says microbiologist Michal Kraus

- The ABCs of writing: Why did its invention mark a turning point for humankind?

- We learn, remember, forget… What can memory actually do? And can we outsmart it?

- New Center for Electron Microscopy in Brno opens its doors to global science

- The hidden lives of waste: What can we learn from waste workers and pickers?

- A unique lab is hidden right beneath Prague’s Vítkov Hill

- Renewables are a strategic investment in European security, scientists say

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.