Citizens of no man’s land

31. 07. 2024

Between March 1938 and September 1939, tens of thousands of Jewish men, women, and children struggled to survive in the forests, fields, and abandoned buildings of Central Europe’s literal borderlands. They were involuntarily inhabiting “no man’s land,” a lesser-known chapter in the history of the Holocaust.

On 17 April 1938, Aladar Reissner along with his 65-year-old mother, his young wife, and their two small children were awakened by the Gestapo in the middle of the night. The family’s passports had already been confiscated, and that night, Reissner was brutally beaten, called “Jewish swine,” and forced to “voluntarily leave the country illegally across the border.” Like the Reissners, all Jews were expelled from the Austrian village of Kittsee in northern Burgenland near the Czechoslovak border. This occurred a mere few weeks after the Anschluss, which saw Austria annexed to Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938. The Gestapo transported the group by truck from Kittsee to the Danube River and, using fishing boats, sent them over to an island on the Czechoslovak side. “It was pitch dark. It was just about freezing, too. We had no coats. Some women were wearing nothing but nightgowns,” Reissner later recounted to American journalist Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker in a news story on the first “no man’s land.”

What are no man’s lands?

“No man's lands emerged in 1938 along the borders of Central and Eastern Europe. These were places of abandonment, immense suffering, and extreme exclusion,” explains historian Michal Frankl from the Masaryk Institute and Archives of the Czech Academy of Sciences (CAS). Frankl is the author of the book Občané země nikoho: Uprchlíci a pohyblivé hranice středovýchodní Evropy 1938–1939 (Citizens of No Man’s Land: Refugees and Shifting Borders of Central Eastern Europe 1938–1939).

“For both those who got trapped in them as for border guards and humanitarian workers, these no man’s lands came as a shock. They represented something that didn’t belong in their vision of civilized Europe, and no one knew how to handle it. State officials lacked the language to describe these areas,” Frankl continues.

Everyone turned a blind eye to the existence of no man’s lands and washed their hands of responsibility. “The German guards opened the gate, and we were supposed to quietly cross over into Poland,” James Bachner recalls about October 1938 in his book My Darkest Years: Memoirs of a Survivor of Auschwitz, Warsaw, and Dachau. The Polish border guards refused them entry, coming out of their guardhouse with weapons drawn. The German patrol behind them, meanwhile, had dogs and fired warning shots into the air.

The fifteen-year-old Berlin native, James Bachner, with Polish roots, was one of approximately 17,000 Jews living in the German Reich deported by the Nazis to the eastern border during the Polenaktion (Polish Action) at the end of October 1938.

Citizens – but only provisionally

Stories similar to those experienced by Aladar Reissner at the Austrian–Czechoslovak border and James Bachner at the German–Polish border also transpired between the Sudetenland and the Czech inland areas after the Munich Agreement (September 1938) and at the Czechoslovak–Hungarian border following the First Vienna Award (November 1938).

Jewish refugees who were forced to leave the Sudetenland after the Munich Agreement (photo from Frankl's book, page 170). Photo credit: The Wiener Holocaust Library Collections.

These forced relocations affected tens of thousands of Jews, many of whom lost their passports and citizenship. For instance, both James Bachner and his brother were born in Berlin after World War I, but their parents were from Poland, and thus the whole family held Polish citizenship. As “foreign elements,” the Nazis expelled them en masse, yet Poland did not want to allow its own citizens into the country either.

In March 1938, the Polish parliament hastily passed a law stripping many Poles living abroad of citizenship. Czechoslovakia began its own citizenship review in January 1939, targeting people from the Sudetenland. Both measures stemmed from the fear of Jewish citizens returning to their home countries.

“We can see this revocation of citizenship as a form of metaphorical no man’s land,” Frankl notes. Jews lost their status as Polish or Czechoslovak citizens without gaining citizenship elsewhere, leaving them stateless and unprotected.

Curiously, the Czechoslovak citizenship review is a relatively unexplored chapter of modern history. “Neither historians nor legal scholars have delved deeply into it, even though it’s a significant event that highlights an ethnocentric shift in how citizenship was perceived,” Frankl says. The harsh measure was hastily prepared, poorly formulated, and inadequately explained, leading to much confusion and uncertainty.

“The Provincial Office in Prague, by a decree dated 9 June 1939, No. 11268 of 1939, refused to grant the following under Section 5 of the Government Regulation of 27 January 1939, No. 15 Coll.; the confirmation of citizenship of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia to Irma Kleinová, a teacher,” reads a brief official notice, now preserved in the National Archives of the Czech Republic.

We do not know how many of the (up to) 30,000 people who were required to apply for Czechoslovak citizenship review shared a similar fate to the above-mentioned teacher. Overall official figures are not available because the Protectorate authorities quietly halted the review process after one year. “The Nazis insisted on its termination – not to protect Jews, but because they were questioning the Protectorate’s sovereignty and its authorities’ ability to decide on citizenship,” Frankl explains.

|

Mgr. Michal Frankl, Ph.D.

Michal Frankl studied political science and modern history at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University Prague). From 2008 to 2016, he worked at the Jewish Museum in Prague, and since 2016, he has been working at the Masaryk Institute and Archives of the CAS. He has completed fellowships at the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, and the JDC Archives. Frankl is the author of numerous scholarly articles in academic journals and has contributed to several international monographs. Along with Miloslav Szabó, he co-authored Building a State Without Antisemitism: Violence, Loyalty Discourse, and the Creation of Czechoslovakia (2015), and with Kateřina Čapková, he co-wrote Uncertain Refuge: Czechoslovakia and Refugees from Nazism, 1933–1938 (2008). In 2023, with the support of the Czech Science Foundation, Frankl’s book Citizens of No Man’s Land: Refugees and Shifting Borders in Central-Eastern Europe, 1938–1939 was published. |

The towboat on the Danube River

The Reissner family, along with other Jews from Kittsee, spent one night on the Danube island. The next day, Czechoslovak police officers sent them towards the point where the borders of Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Hungary converged. “We walked slowly because the elderly among us kept collapsing. I had to carry my four-year-old child while my wife carried our youngest,” the young father recalls in the report by the US journalist.

The following night, the Hungarian side sent the group back to Czechoslovakia in the same manner, and the scenario repeated for another three days and nights. The elderly gradually couldn’t go on, the younger ones’ feet were bleeding, and the children were feverish. Meanwhile, the tripoint where the group kept wandering back and forth was within sight of their home village.

Upon hearing of the situation, members of the Jewish Orthodox community in Bratislava provided assistance to the exhausted Burgenlanders. They rented a tow cargo boat owned by a French shipping company for the refugees to move into. The (Jewish) director of the shipping company, a local, had the boat equipped with straw mattresses, pillows, blankets, and lanterns.

Around six dozen refugees had to survive for several months on a towboat on the Danube River. Photo credit: Suzanne Steinberg family archive.

The boat was docked on the Hungarian side of the Danube, connected to the shore by a bridge guarded by the gendarmerie. Key aspects of care were handled by Jews living in Bratislava, while food and daily necessities were supplied by Jews from a nearby village.

“This story illustrates how no man’s lands were created not by decisions made by states, but by refugees wandering along the border. They became unintended spatial manifestations of violent expulsions and the merciless closing of borders,” the historian notes.

The presence of the boat with refugees attracted attention, possibly because it was the first such case. Both humanitarian workers and journalists took an interest. However, the people on the barge felt forgotten and excluded from society, becoming persons without names or identities.

There were few options how to help the displaced. They could not return home, and neighboring countries refused to accept them. The only solution was to emigrate off the continent, which was impossible without documents. Regardless, humanitarian workers attempted to aid this nearly impossible goal. After much negotiation, they managed to gradually transport all the boat’s inhabitants away, with the last group leaving in September 1938. Some succeeded in emigrating to Palestine, others to South America, and many to the USA – like the family of Aladar Reissner.

In-between Poland and Germany

The case of the Danube boat is exceptional. It was the first of its kind, receiving much attention, and due to the relatively small number of people involved (approximately sixty), all were saved. Unfortunately, most of the tens of thousands of Jewish refugees did not have such luck.

The largest no man’s land was the town of Zbąszyń, located on the Polish-German border before World War II. From the evening of 28 October 1938 until the following afternoon, seven trains carrying about 3,000 involuntary passengers arrived at the local railway station. The waiting rooms and platforms were filled with exhausted refugees, with more arriving later. Many had endured long processions and days spent between the border lines.

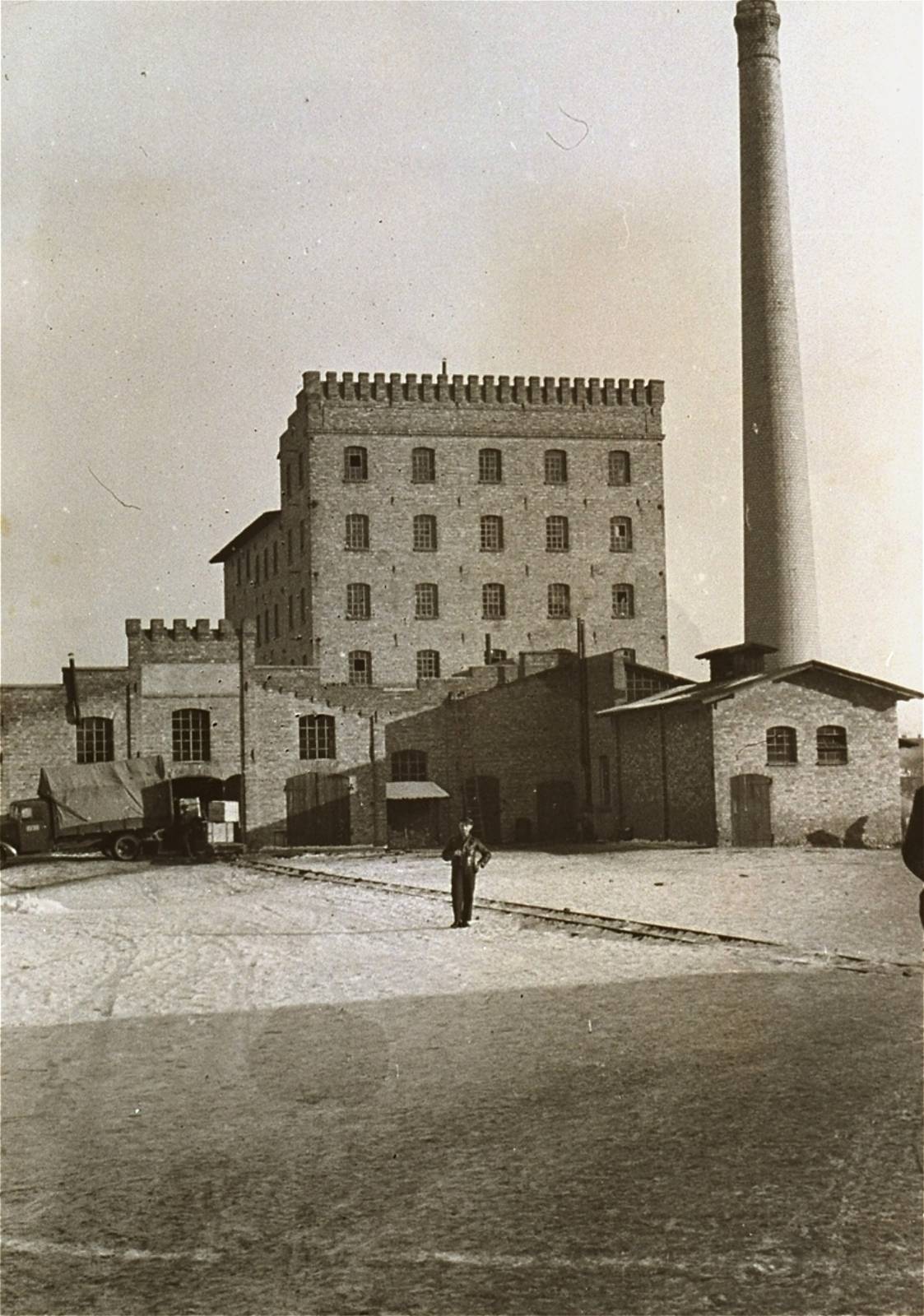

The detention of thousands of Jewish refugees in Zbąszyń, a town with 5,000 permanent residents, initially intended to last only a few days, stretched to ten months. Some found shelter in former stables near the barracks, others in a multistory building of an old mill, and those with some means rented out rooms with local families.

Some managed to break through the blockade and reach the Polish interior to stay with relatives, gradually reducing the number of refugees in the town. In the summer of 1939, the Polish government decided to end the blockade, and the last refugees left just before 1 September, as Germany’s attack on Poland marked the beginning of World War II.

The subsequent fates of the Zbąszyń Jews intertwined with the fates of other Jewish populations in Poland, with many perishing in concentration and extermination camps. The few surviving testimonies of Zbąszyń come from children who were saved through the Kindertransport rescue operations to Great Britain.

View of the flour mill in Zbaszyn, Poland, which served as a refugee camp for Jews expelled from Germany. Photo credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Michael Irving Ashe.

Terezín and Ivančice

Later recollections from Jewish children and adolescent survivors helped reconstruct events after the Munich Agreement along the borderlines between the Sudetenland and the Czech interior. Further “geographical traps,” which were difficult to escape from, appeared near Břeclav in southern Moravia, between (Sudeten) Lovosice and (Czech) Terezín, and in other places.

Gerard Friedenfeld, the son of a local merchant, along with his mother and a hundred other Břeclav Jews, found themselves “abandoned” by an unfinished concrete road just outside their hometown. He remembered the forests lining the border well from early childhood, associating them with outings with his parents when they would go wild strawberry picking. Suddenly, the same area had transformed into a brutal, hostile, uninhabitable place.

It was mid-October. The nights were already cold, and entire families were sleeping by the roadside within sight of their own town, with German and Czech guards exchanging gunfire over their heads. For three days, the groups hid behind pieces of furniture they had brought with them. This was just one of at least three no man’s lands around Břeclav – others were located between Pohořelice and Dolní Kounice.

In November, additional no man’s lands appeared in western and northern Bohemia. Near a dirt road outside the town of Louny, which remained part of Czechoslovakia after Munich, a group of thirteen refugees from the Sudetenland scraped by for three weeks. An improvised shelter provided some relief, along with by a caravan delivered later by the Red Cross.

Stray groups from various places along the northwestern border between the Sudetenland and Czech inland areas later found temporary refuge in the former fortress and barracks of Terezín. Exiles, particularly from southern Moravia, moved to Ivančice near Brno – as did Gerard Friedenfeld.

“Rooms are being prepared in the rear building of the former tannery for the Jews,” notes the Ivančice chronicle entry from 8 November 1938. The facility was equipped by Jewish organizations from Brno – they had rusty machinery cleared out, the basement converted into a kitchen and laundry room, the first floor turned into a dining room, and the upper floors furnished with bunk beds.

By January 1939, about five hundred people were living in the Ivančice shelter. Their living conditions drastically worsened after the German occupation in the spring of 1939, when the Gestapo took over and turned it into a concentration camp.

Moments associated with the arrival of the Gestapo were recorded by Gerard Friedenfeld. “He describes a lineup accompanied by humiliation. Along with other young men, he was forced to repeatedly climb a ladder and jump off it until he broke his leg. He then had to crawl to the infirmary on his own,” Frankl says. The young man eventually survived the Holocaust thanks to the Kindertransports to Great Britain.

No man’s lands today

Groups of people wander through the swampy forested land along the Polish-Belarusian border. Belarusian border guards are urging them to cross into Poland, while Polish soldiers refuse to let them in. The old, the young, children, entire families. Desperate people who cannot go back or ahead, trying to overcome barbed wire to reach safety.

But it is not 1938 or 1939. This is the current situation of the last few years, months, and days. Refugees from the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan, northern and sub-Saharan Africa, all trying to cross the tightly guarded borders of (not only) the EU. No man’s lands are not a thing of the past.

“This situation didn’t start in 2015 with what is called the migration crisis. Similar situations were already occurring before, sometimes even in the very same places decades ago. History never repeats itself exactly, but events are often similar in many aspects, allowing us to think in broader contexts,” Frankl notes.

Michal Frankl's book, Citizens of No Man’s Land: Refugees and Shifting Borders in Central-Eastern Europe, 1938–1939.

While writing his book Citizens of No Man’s Land, Frankl visited the tri-border area between Slovakia, Hungary, and Austria. Today, finding the exact spot where the boat of Burgenland exiles was moored in 1938 is impossible, as the landscape has changed (partly due to the construction of the Gabčíkovo–Nagymaros waterworks). However, its genius loci is still evident, the area dotted with memorials. Most of them, however, pertain to the Iron Curtain and its dismantling in 1989. Memories of this short but crucial period for Holocaust history have been overlaid by additional layers of events.

“Right at the border tripoint stands a stone memorial from the 1990s. It’s a bit worn now. Even though the borders are open, the Austrian army occasionally patrols the area. The border has taken on a new, different kind of symbolism,” Frankl concludes.

We tend to view borders between states as fixed lines drawn on a map. However, they tend to change and shift, with states competing and sometimes even going to war over them.

But do borders represent a wall behind which all dialogue ends? Can a state renounce responsibility for what occurs just beyond its official borders? Should a nation-state consider its position on the map in an isolated manner? Looking at the events of 1938 and 1939 along Europe’s ever-shifting and uncertain borders might offer us the opportunity to reconsider our current and future challenges in a broader context.

Written and prepared by: Leona Matušková, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Shutterstock; The Wiener Holocaust Library Collections; Suzanne Steinberg family archive; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS; Nakladatelství Lidové noviny

While the text is released for use under the Creative Commons license, the photos are subject to copyright as credited.

While the text is released for use under the Creative Commons license, the photos are subject to copyright as credited.

Read also

- A trapped state: The pandemic impact on public attitudes, trust, and behavior

- Aerial archaeology: Tracing the footsteps of our ancestors from the sky

- Archaeologists uncover ancient finds along Prague Ring Road

- Our microbiome largely depends on what we eat, says microbiologist Michal Kraus

- The ABCs of writing: Why did its invention mark a turning point for humankind?

- We learn, remember, forget… What can memory actually do? And can we outsmart it?

- New Center for Electron Microscopy in Brno opens its doors to global science

- The hidden lives of waste: What can we learn from waste workers and pickers?

- A unique lab is hidden right beneath Prague’s Vítkov Hill

- Renewables are a strategic investment in European security, scientists say

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.