Straws as a symbol of pollution: single-use plastic products are on their way out

27. 09. 2022

In August 2022, an amendment to the law on limiting the environmental impact of certain plastic products came into force. The amendment bans the use of single-use straws, cups, cutlery, cotton buds, and helium balloon holders. How do experts view the new restrictions, which are based on EU regulations? Is it a step in the right direction? We asked researchers Zdeněk Starý and Hynek Beneš from the Polymer Processing Department of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the CAS for their opinion on the issue.

The domain of both researchers is research and development of polymeric materials, which also include plastics. They are, for instance, conducting research in recycling and materials from renewable sources which could replace single-use plastics. In their view, current alternatives to single-use products are not always the best option.

The amendment in question, which came into force in August 2022, bans the production and sale of certain single-use plastic products, with the aim of reducing the amount of produced plastic waste. What do you think of the new regulations?

Zdeněk Starý: In principle, it is a step in the right direction. Reducing waste is definitely desirable. Unfortunately, drinking straws and similar plastic products have become the flagship of this change. They are essentially insignificant in terms of the total volume of waste generated, just like products such as disposable plastic tableware, which can be easily sorted and recycled if properly managed.

Do we even know how high the consumption of plastic straws, which have become the symbol of the whole change, is? Are there no other products which fare worse in this respect?

Zdeněk Starý: I’m afraid there are no reliable statistics on the consumption of plastic straws. The impetus from the EU to ban plastic straws and cotton buds arose from the fact that they account for approximately two, respectively ten percent of the waste collected from beaches. It should therefore be taken into consideration that these products constitute a large proportion of waste found on European beaches. By the way, cigarette butts make up the largest amount of plastic waste on beaches – almost twenty percent. They are followed by plastic bottles and caps at eighteen percent and food packaging and candy wrappers at eight percent.

There are alternatives to most single-use plastic products that should be more eco-friendly. Is this really always the case?

Hynek Beneš: It may not always be. Disposable plastic cups for hot drinks are now made from paper covered with plastic film. This is a paper/plastic composite product, which is much less recyclable than the plastic cups that had been used before, which are 100% made from just one type of plastic. Moreover, so-called LCA studies, i.e., life cycle assessment studies, often show that other single-use alternatives to plastic products place a greater burden on the environment. For instance, paper production is a raw material and energy intensive process which also produces large amounts of wastewater that needs to be treated. Similarly, the joy of an ‘eco-friendly’ bamboo straw can be spoiled by the fact that this basically (usually) unnecessary product had to travel halfway around the world to reach us, contributing to the pollution of the seas and oceans. Overall, it is the single-use aspect of the product which is problematic. Such a product is not eco-friendly, no matter what it is made of. A reusable product will always be greener than a single-use counterpart.

Researchers say we should try to limit our overconsumption of disposable products, using them only when absolutely necessary.

Some fast-food chains have started using paper straws instead of single-use plastic ones. Does this make sense?

Hynek Beneš: It makes sense if the fast-food restaurant customer then goes and throws away their used straw in nature, for instance, when on a walk in the forest. There, a paper straw can indeed decompose over time thanks to microorganisms found in the soil, but it will take quite a long time. However, you probably recognise that this method of ‘disposal’ is not what should be happening. The straw should instead end up in the rubbish bin, the contents of which should ideally be further sorted and processed.

The Czechs are among the top recyclers of PET bottles in Europe, with a sort rate of approximately eighty percent. What happens to the plastic bottles afterwards and what are they used for?

Zdeněk Starý: The Czech Republic is indeed very successful in sorting PET bottles. After the bottles are sorted out of mixed plastic waste, they are usually further sorted according to colour, crushed into so-called flakes, and thoroughly washed to remove contaminants. During this step, the polyethylene cap material is also removed via flotation. PET bottles can be recycled by means of the “bottle-to-bottle” technology, where the resulting material is used for the production of plastic bottles. This technology is the most demanding regarding the purity of the incoming material. A large proportion of the bottles, particularly coloured bottles, are recycled into PET fibres and staple fibres, which are used mainly in technical applications such as carpets, geotextiles, and non-woven fabric. Plastic bottles can also be recycled chemically, which results in raw materials for the production of new PET or other materials.

PET bottles are the most valuable component of plastic waste, as they can be further processed and utilised.

Would it make sense to make PET bottles returnable considering the Czechs are such responsible recyclers? Or would it be an unnecessary burden for retailers?

Zdeněk Starý: The introduction of returnable PET bottles has been gaining more and more supporters lately. However, this would require changes to the waste management system on a deeper level. Currently, every Czech recycles an average of about seventeen kilograms of plastic waste per year, and in recent years, this figure has been slightly on the rise. PET bottles, which make up around a quarter of the plastic waste in yellow bins, are the most valuable component of plastic waste. By sorting and selling PET, recycling companies receive funds they then use to recycle other residual plastic waste. If PET bottles were to disappear from the yellow bins, we can realistically expect a significant decline in the interest of recyclers in mixed plastic waste. Considering the fact that around eighty percent of PET bottles are already being recycled in our country, I would consider it more sensible to further educate the population and improve the availability of places where sorted waste can be handed in. By using this approach, it is certainly possible to increase the number of sorted PET bottles.

So what are the pros and cons of having a system of returnable bottles?

Zdeněk Starý: We cannot ignore the significant costs of building an infrastructure associated with returnable bottles and with introducing a new network for the transport of returned bottles. One undeniable advantage would be the better purity of the PET material. At present, there is a shortage on the market of recycled PET suitable for the production of beverage bottles. Moreover, the EU requires that by 2030, ninety percent of such packaging will have to be sorted, and wants new bottles to contain a minimum of twenty-five percent recycled materials.

So-called bioplastics are seen as a potential alternative to conventional plastics. What are their advantages and disadvantages?

Hynek Beneš: In the case of plastics, the prefix bio- is used in a somewhat confusing manner both for materials made from renewable sources and for materials that are naturally degradable. In the first case, we need to evaluate whether it is actually beneficial to grow, for example, corn to produce plastics instead of food for an ever-growing population. In the second case, we need to recognise that biodegradable plastics can make it much more difficult to recycle mixed plastic waste and do not, in any case, belong in the yellow bin. Their use thus places increased demands on ordinary citizens and industrial sorting systems to sort plastic waste.

In recent years, we have seen the emergence of packaging-free shops. Packaging-free or zero waste shopping is even promoted by some large chains. Could you imagine a way how to motivate not only consumers, but also companies, manufacturers, and retailers, to implement this concept (even if only partially)?

Hynek Beneš: For many products, especially food and drugstore goods, packaging is often irreplaceable. It prolongs shelf life, enables transport, etc. If the use of packaging can be avoided, it is desirable to motivate consumers, especially by highlighting the economic advantage of the packaging-free alternative, i.e., its lower price. Motivating manufacturers is more difficult, as for them, ‘packaging sells’. The solution could be, for instance, to tax disposable packaging.

In the past couple years, packaging-free or zero waste shops have also been appearing in the Czech Republic.

Do you see any other options?

Hynek Beneš: Another important component of the whole strategy to reduce single-use packaging is education, which can lead to a change in consumer behaviour. For instance, do I really need to have my goods delivered via an e-shop where they will wrap them in several layers of packaging? Do I really want products that are made on the opposite side of the world and which must be wrapped in packaging to transport them? Perhaps increased awareness and asking ourselves such questions is the right way forward to reduce the burden on the environment – and not just with plastic packaging.

________________________________________

ReMade: targeting the circular economy

A circular economy is based on production efficiency and aims to improve the quality of the environment. Simply put, it strives to keep utilised resources and raw materials in circulation for longer and reduce waste, thus preventing the rapid depletion of our planet’s natural resources.

“Nowadays, there is production of a lot of single-use products, which creates problems. Once a product is used, it has to be thrown away. But then the question arises, throw away where? The second issue is that we consume raw materials and energy,” explains Martin Kalbáč from the J. Heyrovský Institute of Physical Chemistry of the CAS, who is the coordinator of the ReMade@ARI project for the Czech Republic, a pan-European platform bringing together around fifty large research infrastructures.

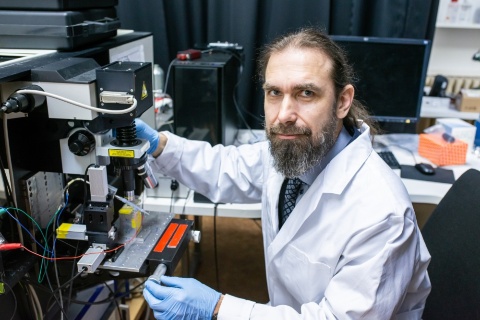

The consortium comprises a platform for researching new processes and products that are 100% recyclable and eco-friendly. “The institutions involved usually have at their disposal expensive scientific instruments and experts who can use them and interpret the results. The instruments and expertise can then be made available to other researchers or industry,” Martin Kalbáč adds. The new materials, which could be an alternative to, for instance, the currently overused plastic products, should thus contribute to the protection of the environment and nature’s resources in the future.

Physical chemist Martin Kalbáč is Head of the Department of Low-dimensional Systems at the J. Heyrovský Institute of Physical Chemistry of the CAS.

Prepared by: Markéta Wernerová, Division of External Relations, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, Division of External Relations, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Shutterstock; Jana Plavec, Division of External Relations, CAO of the CAS

The text is released for use under the Creative Commons licence.

The text is released for use under the Creative Commons licence.

Read also

- From an evolutionary POV, vision has a great benefit–cost ratio, researcher says

- Badminton buzz: Tournament draws 76 athletes from the Academy’s institutes

- Unique reproductive strategy confirmed in another frog species in Moravia

- Hydrochemist Martin Pivokonský on how to improve water and wastewater treatment

- Involved in groundbreaking research, Ukrainian archeologist now works at the CAS

- The first human presence in Europe securely dated to 1.4 million years ago

- The CAS visited by chess grandmaster and Russian opposition activist Kasparov

- The CAS will support scientists whose research is at risk in their home country

- Unravelling the mystery of biodiversity – with a little help from the fruit fly

- The Academy hosted a two-day UK–Czech Republic Bilateral International Meeting

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.