Could an asteroid hit Earth? The risk is low, but astronomers are keeping watch

19. 01. 2026

At the heart of every defense strategy is thorough preparation. It helps to know your adversary, too – especially when that adversary is an extraterrestrial body capable of striking with the force of a nuclear bomb. Astronomer Petr Pravec from the Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences and his colleagues carefully monitor threats from space. You can read about how this planetary watch works in the following article, published in A / Magazine.

The Yucatán Peninsula in the Gulf of Mexico hides the partially preserved Chicxulub crater, roughly 180 kilometers wide and – in certain spots – as deep as 20 kilometers. About 66 million years ago, an approximately ten-kilometer-wide asteroid gouged this giant scar into Earth’s surface. The enormous environmental changes that followed wiped out three-quarters of animal species, including most dinosaurs, from our planet. That’s the catastrophic side of the story. Now the reassuring part: similarly devastating collisions only occur on average about once every 100 million years.

But much smaller objects that penetrate Earth’s atmosphere can still cause significant damage. On the morning of 30 June 1908, a fifty-meter-wide asteroid exploded over the Siberian taiga, flattening and igniting forests over an area exceeding 2,000 square kilometers. The blast – estimated at around 30 megatons of TNT – was 2,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Thanks to experiences like these, the informed part of humankind is acutely aware of how vulnerable life on this planet is. In recent decades, scientists have invested considerable effort into studying near-Earth objects, including those that are potentially hazardous. Part of this global planetary watch are teams of researchers worldwide who keep their eyes fixed on the night sky. One of these “watchers” is Petr Pravec from the Astronomical Institute of the CAS in Ondřejov, discoverer of more than three hundred asteroids and an expert in determining detailed properties of these objects.

Petr Pravec from the Astronomical Institute of the CAS in Ondřejov. (CC)

ASTEROIDS IN THE CROSSHAIRS

The word asteroid originally comes from the Greek language and loosely translated means “star-like.” In the 20th century, astronomers began calling these Sun-orbiting objects minor planets. The catalog of asteroids – or minor planets – is regularly updated and, by July 2025, contained nearly 1.5 million entries. Of those, more than 38,500 asteroids are classified by NASA’s planetary defense team as potentially hazardous, meaning they’re worth monitoring closely.

For a time, the asteroid designated 2024 YR4 appeared in this group. U.S. scientists spotted it a few days after Christmas at the observatory in Chile, and NASA’s preliminary calculations suggested that the asteroid had a small – but nonzero – chance of hitting Earth on 22 December 2032. Since then, astronomers have been tracking the object and carefully logging any changes in its risk profile. Petr Pravec also has 2024 YR4 on his watch list, supported in his long-term research on minor planets by the Academic Award bestowed by the Czech Academy of Sciences.

|

SCIENCE MINUS THE RED TAPE The Academic Award – Praemium Academiae is the top research award bestowed by the Czech Academy of Sciences to outstanding scientists. Recipients typically praise its minimal administrative burden, and Pravec, who received the prize in 2024, echoes that view. With its support, he is planning to stabilize and expand his team and focus on research with less paperwork. “In a certain sense, it’s the best grant I’ve ever received. It allows me to concentrate on science rather than on administrative matters and constant fundraising,” the astronomer says. |

THE MOON AT RISK?

“Every year, we plan to monitor several dozen objects,” Pravec says. “I hope none will turn out to be genuinely dangerous in the sense of having a significant probability of hitting our planet. However, we need to keep an eye even on those that show relatively small chances of impact with Earth.”

In the first months of 2025, astronomers proved that 2024 YR4 would not endanger Earth. However, newly computed orbital paths show about a four-percent chance the asteroid could hit the Moon in December 2032. Ejected material from such an impact could, in theory, jeopardize artificial satellites orbiting Earth that are important for everything from spy technology to GPS and weather forecasting.

Current measurements indicate that 2024 YR4 is a typical member of the so-called S-type asteroid class – meaning it’s composed mainly of silicates, the same minerals that make up the majority of Earth’s crust.

The image, created by ESA, shows the orbit of asteroid 2024 YR4 (in red). Recent data projects chances of impact as miniscule.

Size is key to estimating the destructive power of a potential impact. Based on available data, 2024 YR4 measures about 53 to 67 meters in diameter. It also rotates extremely fast, with a period of about 19 minutes, which is common for celestial bodies of this size. “We don’t know yet if it’s a single solid rock,” Pravec explains. “But it definitely has a relatively firm structure, because at its rotation speed, it couldn’t be just a loose gravitational aggregate of smaller pieces.”

Scientists also need to pin down the shape of the asteroid. So far, they know it’s elongated, but not by how much. Very little is known about its density.

REMOTE CONTROL

Of course, researchers can’t weigh or physically sample an asteroid directly. They infer its properties from observations made with telescopes located at sites with excellent atmospheric conditions. The good news is that these telescopes can be operated remotely from almost anywhere, provided you have a remotely connected computer with the appropriate software – and a highly qualified team working closely with international colleagues. Pravec has been studying asteroids for more than thirty years and has just such resources. For instance, he has long partnered with the University of Copenhagen, which operates a powerful photometric telescope at La Silla Observatory in Chile.

La Silla Observatory is located in the southern Atacama Desert in Chile, far from sources of light pollution.

Pravec’s team in Ondřejov has regularly scheduled observing time with Danish colleagues. They log in remotely to the telescope and control it with scripts prepared specifically for each night of observation. “We enter the object’s coordinates, the observation filter, exposure time, and other parameters into the program. At night, the software runs automatically according to the scenario,” the astronomer explains.

The observers then check whether everything is going according to plan or anything unexpected has occurred and whether any adjustments are needed. Typically, two people split a night’s work – one takes the shift from midnight to 6 AM and the other from 6 AM to noon (Chile is six hours behind Central European Time). Generally, this is relatively routine work. The idea that an astronomer staring at a screen recording the starry sky experiences emotions or surprises like those in a sci-fi film is far from reality.

“Asteroids all basically look the same: a dot in a star field that moves from one frame to the next. We don’t really learn interesting things about them until we conduct a series of measurements and calculations,” Pravec says.

|

NAMING AN ASTEROID What connects Ondřejov, Božena Němcová’s Babička (The Grandmother), Dominik Hašek, and Daniel Stach? Their names are also borne by asteroids discovered by Petr Pravec’s team. The naming of astronomical objects follows clear rules – for instance, names should not be inspired by politicians or military figures, nor should they be commercially motivated. The vast majority of asteroids, however, have no name at all. Nor could they, since there are hundreds of thousands of them, with new ones being discovered practically every day. Most asteroids are designated by a code consisting of numbers and letters with specific meaning. For example, the designation 2024 YR4 signifies that the asteroid was discovered in 2024 in the second half of December (the letter Y), with R4 being its sequential code. |

Astronomers will have to wait a bit longer to learn more details about 2024 YR4. The asteroid approaches Earth in roughly four-year intervals, and the next good opportunity to observe it and obtain high-quality measurements won’t occur until December 2028. And that will also be the last chance to learn more: its subsequent approach to Earth in December 2032 may already be risky.

If the asteroid does not hit the Moon, it will pass very close to it. But all this data still needs to be refined. In any case, if humankind decides not to leave things to chance and to try to deflect the object, work on that would need to begin as early as possible.

THROWING A DART INTO SPACE

Four years ago, NASA successfully tested asteroid-deflection technology as part of the DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) mission, whose goal was to impact the binary asteroid system Didymos–Dimorphos. The carefully calculated collision occurred on 26 September 2022. A spacecraft with a mass of roughly 580 kilograms, traveling at more than 6 kilometers per second, struck Dimorphos, changing its orbital period by a full 33 minutes. (We reported on the DART mission here.)

If it were decided to use the same deflection technology for 2024 YR4, all necessary data on the asteroid’s size, shape, and structure would first have to be available. Another important piece of information is whether the asteroid has a moon. For instance, Dimorphos, which orbits Didymos, was discovered by Pravec’s team in 2003 – almost twenty years before the DART impact.

The moons of asteroids cannot be directly seen in images taken from Earth. Their presence is revealed only through precise measurements. At a certain point, the celestial bodies eclipse one another, causing a drop in brightness that appears in the recorded data. When such events recur periodically, it can be inferred that the observed object has a satellite.

“We developed the methodology for detecting satellites orbiting asteroids many years ago. Since then, we have discovered hundreds of them,” Pravec says. Knowing about the presence of moons is useful not only for potentially hazardous asteroids, but also for those targeted by exploratory space missions. If they were not taken into account, complications could arise during flybys or attempts to land a probe on an asteroid.

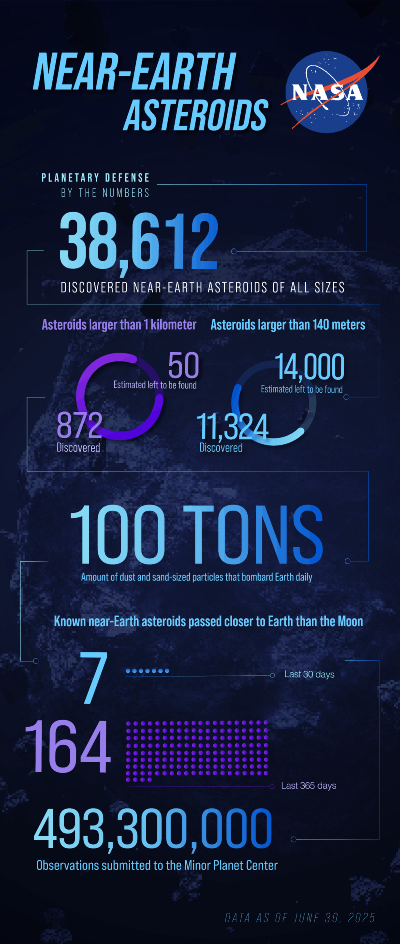

Each month, NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office releases a monthly update featuring the most recent figures on NASA’s planetary defense efforts, near-Earth object close approaches, and other timely facts about comets and asteroids that could pose an impact hazard with Earth. Infographic data as of July 2025. Source: NASA.

ARABIAN ASTEROIDS

The presence of satellites around asteroids is also of interest to organizers of the United Arab Emirates’ EMA space mission. Its aim is to fly through the main asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter and, among other things, determine whether water and other resources are present on the asteroids. The resource potential of asteroids and their possible use in future space exploration are additional reasons why researchers around the world are focusing their attention on these celestial objects.

The UAE mission is planned for the early 2030s. It intends to fly past seven asteroids and land a probe on one of them. For five of these asteroids, the Emirati team will need the maximum possible observational data from the Czech astronomers in Ondřejov. “So far, we know these are so-called primitive asteroids, consisting mostly of carbon-rich compounds. They might contain water bound in minerals,” Pravec explains.

Primitive asteroids have undergone very little change since their formation, so they can reveal important information about the early stages of the Solar System. They range in size from a few to several tens of kilometers. More detailed knowledge is yet to come. For now, we can say, with complete certainty, that these particular asteroids do not pose any risk to Earth.

EARTH (HOPEFULLY) SAFE

Petr Pravec’s team plans to study dozens of celestial objects over the next several years, although the list is more or less provisional and may change depending on new findings. “The fact that we are currently planning to prioritize studying the five asteroids related to the EMA mission, even though they do not pose any threat to our planet, is more of an exception. Whenever a new potentially hazardous object appears, we definitely focus on it first,” the astronomer assures us.

That Earth will face anything like the catastrophic threat posed by the asteroids mentioned earlier in Mexico or Siberia is highly unlikely. At least for now, no scientific observations indicate anything of the sort. Still, the planetary watch remains on alert.

*

|

Mgr. Petr Pravec, Ph.D.

Petr Pravec is the discoverer or co-discoverer of several hundred asteroids (minor planets). He studies their physical properties – both of those that may be potentially dangerous to Earth and those that could serve as sources of raw materials for future space missions. What happens beyond the frontiers of our planet has fascinated him since the age of nine, when he found František Běhounek’s book Robinsoni vesmíru (Robinsons in Space), a seminal Czech sci-fi novel, under the Christmas tree. He studied at Masaryk University in Brno and completed his doctoral studies at Charles University in Prague. An asteroid is named after him: (4790) Petrpravec, discovered in 1988 by American astronomer Eleanor F. Helin. |

*

The article first came out as “Planetary Watch” in the 3/2025 Czech issue of A / Magazine:

3/2025 (version for browsing)

3/2025 (version for download)

All Czech and English issues of A / Magazine – the official quarterly of the Czech Academy of Sciences, including its predecessor A / Science and Research – are available online.

We offer free print copies (of the Czech version and the two English issues from 2024 and 2025) to anyone interested – please contact us at predplatne@ssc.cas.cz.

Written and prepared by: Leona Matušková, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS; Shutterstock; ESA

The text and photos marked CC (and the researcher's bio photo) are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text and photos marked CC (and the researcher's bio photo) are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- Better ECGs and Industrial Superlasers – Real-World Results of CAS Research

- Czech Academy of Sciences to launch a joint-stock company

- In the Age of AI, Spotting a Fake Photo Is Harder Than Ever, Expert Says

- How to Turn Ideas into Successful Grants: The New ERC Incubator Is Offering Help

- SciComm 360° Tackled How to Communicate Science in the Age of Disinformation

- The Academy of the Future? A New Vision for Attracting Scientific Talent

- When Cars Fly and Bullets Swerve – Physics Gone Wrong on the Silver Screen

- The Academy to Boost Excellence and Careers in Research with New Programs

- At the nanoscale, gold can be blood red or blue, says Vladimíra Petráková

- The beauty of Antarctic algae: What can diatoms tell us about climate change?

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Radomír Pánek started his first term of office in March 2025. He is a prominent Czech scientist specializing in plasma physics and nuclear fusion.