Researching scent: Cleopatra’s legacy, Egyptian rituals, and ancient heritage

28. 11. 2025

The Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans alike used fragrant balms, oils, and perfumes in rituals, medicine, and cosmetics. Now, more than 2,000 years later, researchers in Prague are working on “reviving” these ancient scents. The article came out in the 2025 English issue of A / Magazine.

The legendary beauty of Queen Cleopatra was said to have been enhanced by a captivating, all-encompassing fragrance of myrrh, cinnamon, and other exotic substances. She made sure her first meeting with the Roman general Marc Antony would be unforgettable. Cleopatra wanted to make an impression – after all, she needed him as an ally to help her hold on to her faltering rule over Egypt.

Cleopatra VII, the last Egyptian monarch of the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty, was renowned for her interest in perfumes and scented balms. She likely used them not only for adornment, but also to support her health and guard against disease. In fact, she has even been credited with writing a treatise on fragrant ointments – a text later referenced by the Roman physician Galen.

The queen, who took her own life in 30 BCE, was far from unique in her love of fragrances. She was part of an ancient Egyptian tradition, going back hundreds or even thousands of years, of using aromatic substances – primarily for ritualistic and religious purposes, but also for medical and cosmetic ones.

Queen Cleopatra surrounded by the fragrances of flowers and resins, as imagined by the Dutch neoclassical painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema. (Wikimedia Commons)

So what made Egyptian scents so special? Why did ancient philosophers study them, and how did they later influence alchemy and the natural sciences? How can we make sense of ancient recipes preserved in hieroglyphs or in Greek and Roman texts? And is it possible to recreate contemporary versions of legendary ancient perfumes using nothing but incomplete or fragmentary historical formulas?

These questions are being explored by the interdisciplinary team led by Sean Coughlin from the Institute of Philosophy of the CAS. Since 2021, the Canadian researcher has been developing the Alchemies of Scent project, supported by the JUNIOR STAR program of the Czech Science Foundation.

CLEARING THE AIR

Sean Coughlin’s journey into the world of scents began while studying the history of ancient philosophy and medicine at McGill University in Montreal. In antiquity, the preparation of medicines and healing remedies was closely linked to aromatic essences and the production of tinctures and ointments. Ancient physicians believed that diseases were caused, among other things, by impure air (the word “malaria,” for instance, comes from the Latin mal aria for “bad air”). To recover from or ward off illness, they recommended exposure to pleasant aromas.

When, for example, a highly contagious epidemic of unknown origin swept through Rome in the latter half of the second century CE, the imperial physicians sent Emperor Commodus to a countryside palace surrounded by fragrant laurel groves on the Tyrrhenian coast. According to the medical advice of the time, air infused with laurel was thought to offer strong protection against infection. The Greeks and Romans attributed almost magical powers to this aromatic plant – laurel wreaths were given to victors in athletic competitions, and the plant was even recommended as protection from lightning.

Whether the treatment was effective or not, Commodus survived the epidemic – though today, we might attribute his survival more to isolation than to aromatherapy. In any case, the emperor – best known to modern audiences as the villain of the Hollywood blockbuster Gladiator – lived another twelve years before being killed by his enemies.

Unlike the instructions given to the emperor, ordinary Romans received far less effective advice during this epidemic. To protect themselves from the contagious disease, they were told to anoint themselves with perfumed oils, burn fragrant incense, and stuff their nostrils and ears with aromatic spices. According to the historian Herodian, as many as 2,000 Romans were dying each day from the illness.

Key ingredients in Egyptian and ancient perfumes included various resins (such as myrrh), cinnamon, cardamom, calamus, as well as flowers like lilies. (CC)

SCENTS AS A SOCIAL MARKER

Fragrance played a crucial role in ancient societies – even in everyday social interactions. One’s scent could indicate social status; wealthier individuals could afford frequent baths, visits to public bathhouses, and luxurious perfumes, while the poor relied on simpler, more affordable fragrances – or none at all.

The importance of perfumes is also reflected in ancient Greek literature. Comedies often featured men adorned with fashionable Egyptian fragrances or depicted young men loitering in the streets of Athens near perfume shops. Even the philosopher Plato mentions perfumes and their role in an ideal society in his Republic.

But what is it about scents that makes them so influential? Biologists might discuss olfactory communication signals, pheromones, receptors, and neurons. Chemists will talk about volatile compound molecules and the reactions between different substances. But how does a philosopher approach scent? And what fascinates them about it?

“For me, scent raises fundamental philosophical problems,” Coughlin says. “How can we perceive something that no longer exists, like incense after it has burned away, and yet fail to perceive what is still present once we’ve grown used to it? These are familiar experiences, but they unsettle our everyday ideas about perception and our access to reality.”

There are many unknowns to uncover. How did people produce perfume before the distillation method was developed in the ninth century? Who was involved in making them? And how did advancements in perfume-making techniques contribute to the development of the natural sciences, particularly chemistry?

|

Sean Coughlin, Ph.D.

Sean Coughlin studied ancient philosophy at McGill University in Montreal and Western University in Ontario. Between his studies, he worked for a year as a cook to better understand culinary metaphors in Aristotle’s biology. Coughlin completed research fellowships at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Humboldt University in Berlin. He contributed to the reconstruction of Queen Cleopatra’s perfume, which was presented at the Queens of Egypt exhibition at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C. Since 2021, he has been the principal investigator of the Alchemies of Scent project, funded by the Czech Science Foundation under the JUNIOR STAR program. Coughlin is working on the project with the Chemistry of Natural Products research group at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the CAS. |

THE ALCHEMY OF SCENT

“At the start of the process, you have ordinary olive oil, and at the end, you have a liquid that smells like roses or lilies. Transforming oils into fragrant substances is, in a way, a form of alchemy,” Coughlin explains, referring to the name of his research project, Alchemies of Scent.

The researcher, who previously worked at Humboldt University in Berlin, appreciates the opportunity to pursue his work in Prague. “The alchemists at the court of Emperor Rudolf II were searching for the elixir of life. In a way, you could say we’re doing something quite similar – trying to revive long-lost methods of producing fragrant essences,” he adds.

But why do we speak of “lost methods” when written records of them have survived? It’s because many of the ancient texts contain words that, after so many centuries, are no longer understood. The terminology varies from author to author, and the instructions often fail to include the full, precise procedure.

It’s a lot like trying to follow a great-grandmother’s recipe. An experienced cook likely wouldn’t have written down every detail because the process was second nature. But if we can no longer call her for advice, we’ll never recreate the dish exactly – we’ll have to improvise.

This analogy with cooking is no coincidence. As a student, Coughlin felt that merely reading ancient texts wasn’t enough to truly understand them. To do so, he believed, one had to “get their hands dirty” and try every process out in practice. That’s why he took a year off from his studies to work as a cook. And this experience turned out to be pivotal for his academic journey.

IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME

Exploring the world from different angles has proven invaluable. Perhaps that’s why Coughlin designed his “perfume project” with an interdisciplinary approach in mind. Understanding the ancient techniques of perfume production and their sociocultural context thus involves a team of experts across disciplines – Egyptology, chemistry, botany, archaeology, and even IT. Their focus is on a specific period between the fourth and first centuries BCE, framed by Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt in 332 BCE and the death of the last Ptolemaic queen, Cleopatra VII, in 30 BCE.

This was a time of intense cultural exchange. Both Greeks and Romans admired Egyptian expertise in perfumery, healing ointments, and fragrant oils. Much of the Mediterranean world was connected, with languages, influences, and traditions intermingling. The powerful Greek and rising Roman civilizations were deeply fascinated by the cultural wealth of ancient Egypt and sought to emulate it. Thanks to the writings of ancient scholars, much of this Nile kingdom’s heritage has survived – including perfume recipes.

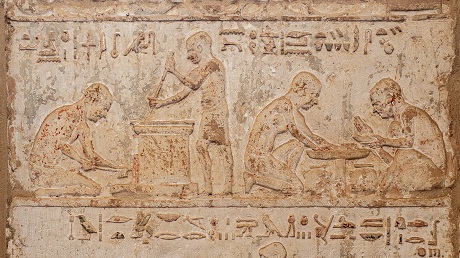

In addition to Greek and Roman texts, a handful of original Egyptian sources also exist, though they are challenging to interpret. “Most of the ancient Egyptian recipes for what we might call ‘perfume’ survive as inscriptions on the walls of Ptolemaic temples. If we exclude medical texts, which have their own specific context, there are very few similar examples on papyri or other materials,” says Diana Míčková from the Institute of Philosophy of the CAS and the Czech Institute of Egyptology at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University.

|

Mgr. Diana Míčková, Ph.D.

Diana Míčková studied Egyptology at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague. She currently works in the Department for the Study of Ancient and Medieval Thought at the Institute of Philosophy of the CAS and at the Czech Institute of Egyptology at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University. She regularly takes part in archaeological expeditions in Abusir. Her research focuses on translating and analyzing religious texts. Míčková teaches Egyptian language and literature, and publishes studies on religious texts, magic and rituals, Egyptian literature, and the ancient art of memory. Together with Dorotea Wollnerová, she co-authored the book Poslyš vyprávění z časů tvých otců (Hearken to Stories from the Time of Your Ancestors), which consists of tales from ancient Egyptian literature. |

The most interesting research for the project is centered on the Temple of Edfu. One of its halls – known as the “laboratory” – is decorated with reliefs and texts depicting the offering of fragrances to the gods, ritual scenes with annotations, recipes, and an extensive list of various resins and aromatic woods.

The actual recipes inscribed on the walls are often complex. “Producing such a ‘perfume’ could take several years and involved many ingredients and steps. For instance, the recipe for an Egyptian ‘oil’ called medjet begins by describing how to raise and then slaughter a bull, whose fat was to be used after a year to form the base of the product,” Míčková explains.

In the Ptolemaic era, Egyptian perfumes were a symbol of luxury. “The Greeks and Romans adored them, considered them highly fashionable, and wanted to smell like Egyptians,” Coughlin notes. Producing Egyptian perfumes was likely expensive, as many ingredients had to be imported from both near and distant lands.

The Mendesian perfume, a blend of myrrh, cinnamon, and other ingredients, was no exception. This was the ancient equivalent of Chanel No. 5, with which Cleopatra probably captivated Marc Antony.

A scene of perfume production from the tomb of Petosiris in Tuna el-Gebel.

EGYPTIAN CHANEL NO. 5

The Mendesian perfume takes its name from the city of Mendes, located in the Nile Delta. Thanks to its strategic location, Mendes had access to exotic spices and resins brought by traders from distant lands. The Egyptian city is explicitly mentioned in ancient Greek and Roman texts in connection with perfumery, and its fragrance-making history is further confirmed by modern archaeological research at Tell Timai, which partially overlaps with the ruins of Mendes.

A team led by Robert J. Littman from the University of Hawaiʻi and Jay Silverstein from Nottingham Trent University uncovered objects at the site that may have been part of a perfume factory. Among the finds were kiln remains that were 1.3 to 1.7 meters in diameter – possibly used to produce perfume bottles – along with silver jewelry and Ptolemaic coins dating from 110 to 61 BCE.

Coughlin established contact with these archaeologists while working in Berlin. Together with Dora Goldsmith, he embarked on the first experimental replication of the Mendesian perfume. The resulting perfume was unveiled in 2019 at the Queens of Egypt exhibition at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C.

In his current Alchemies of Scent project, Coughlin aims to revive the production of five fragrances: in addition to the Mendesian perfume, these include the Metopion and susinum perfumes, the myrrh-based oil stakte, and a smoked oil that is to be created using a technique resembling distillation.

|

THE SCENT OF CHRISTMAS

Cinnamon, cloves, star anise, vanilla, fresh pine needles, and roasted apples… The smells of Christmas can induce feelings of togetherness, calm, and peace (once the frantic baking and preparations are over). In ancient Egypt and Greece, however, these aromas carried a very different meaning. “The Mendesian perfume had a strong scent of myrrh and cinnamon. Today, it might remind us of holiday cookies or gingerbread – but in antiquity, it was a sexy, provocative fragrance,” Sean Coughlin says. The raw materials used for perfumes were exotic, expensive commodities imported from afar. So when the Gospel of Matthew claims that the Three Wise Men brought myrrh and frankincense to the infant Jesus, these were indeed precious gifts. But if we’re imagining biblical Bethlehem filled with the scent of cinnamon and vanilla, we’re likely far from the truth. It probably smelled more of goats, sheep, donkeys, and unwashed people. Reality is sometimes grittier – and more pungent – than the idealized picture. |

AN ADVENTUROUS JOURNEY

The ultimate goal of the researchers isn’t, of course, to become perfumers or to bring back ancient recipes to today’s fragrance market, but rather to understand the processes and connections behind the production of ancient perfumes. In addition to studying Greek and Roman philosophical and literary texts and ancient Egyptian inscriptions, uncovering the chemistry behind the recipes has also proven to be crucial.

“For me as a chemist, this project is truly a dream come true. I absolutely love the whole adventure of trying to recreate an ancient perfume,” says Laura Juliana Prieto Pabón, a PhD student originally from Colombia, involved in the Chemistry of Natural Products group at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the CAS.

In organic chemistry, the goal is usually straightforward – the synthesis of a particular molecule. “But when you’re trying to replicate an ancient perfume recipe, you don’t know what the final result should look like. In fact, you have no idea what it actually smelled like to people back then. So you go through the process and try to understand what’s happening from a chemical point of view,” the young scientist explains.

Take the Mendesian perfume, for instance – one of the trickiest parts turned out to be the mysterious oil called balaninon. It may have been made from the moringa tree, which grows in areas that are now the Sinai Peninsula, Syria, or Israel. But we can’t be sure. Not only do we not know exactly what the substance was, the method of preparing the oil for use in perfumery is also unknown – it likely differed from processes used for other purposes. The Greek philosopher Theophrastus (372–287 BCE) suggested heating the oil for ten days and nights to help it better absorb the scents of resins – but this instruction doesn’t appear in other ancient texts.

With the Mendesian (as with any ancient perfume), many uncertainties remain. One of its main ingredients was supposedly myrrh. But which kind? Myrrh is an oleo-gum resin that can come from the sap of various tree species. In ancient times, it was imported to Egypt from what is now Ethiopia and Somalia, from Palestine, and from the Arabian Peninsula – and each time it came from a slightly different tree species.

Cleopatra’s perfume was also said to have smelled of cinnamon. But we have no idea whether it was a variety from India or China, or a local cultivar that resembled cinnamon in scent and taste but came from a different plant altogether.

|

Laura Juliana Prieto Pabón, MSc.

Laura Pabón studied organic chemistry at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá and perfume chemistry at Université Côte d’Azur in France. She is currently pursuing a PhD at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the CAS in the Chemistry of Natural Products group. Her research focuses on organic chemistry and fragrance analysis. Within the Alchemies of Scent project, Pabón is responsible for its chemical component and also actively participates in public workshops on ancient perfume-making. |

THOUSANDS OF LILIES

Seeing gardeners tending to trees and other plants at the Prague Botanical Garden in Troja is nothing out of the ordinary. But in October 2024, a passerby might have been surprised to see just who was poking around in the flowerbeds. Wielding gardening gloves and spades was a group made up of philosophers, chemists, Egyptologists, and other experts who, on a normal work day, have little to do with digging in the dirt. This unlikely team showed up to plant more than a thousand lily bulbs, which will be used to make susinum, one of the most iconic perfumes of antiquity.

If all goes to plan, several thousand lilies will flower from the bulbs. According to a recipe recorded by the Greek physician Dioscorides (40–90 CE), one needs to process a thousand lily flowers a day for three days to make a single liter of susinum (three thousand flowers per liter total).

“This shows just how costly perfume production likely was. If the Egyptians wanted to make a hundred liters of susinum perfume, they needed huge lily plantations, which would’ve been tended by a lot of slaves. It was a massive operation,” Coughlin explains.

The team won’t be making that much perfume, of course. But they do intend to follow all the instructions and methods that can be gleaned from the preserved recipes. So far, they’ve tested only a small sample batch of susinum. This year, working with thousands of flowers ought to be a far greater adventure.

Just like with the previous Mendesian and Metopion perfumes, the researchers will once again invite the public to join their experiments. The project includes workshops where participants can try their hand at ancient perfume-making techniques.

The processing of lilies is expected to yield a pleasant, fresh floral scent – one that modern fragrance wearers might well enjoy. But would Cleopatra have liked it?

Surprisingly, probably not. Just like fashion, fragrance preferences are shaped by cultural trends. “Texts suggest that in antiquity, floral perfumes were typically favored by men, who liked the smell of lilies and roses, while women tended to wear heavier, resinous perfumes with the scent of myrrh and cinnamon,” Coughlin explains.

The Alchemies of Scent project also includes public workshops where participants can create perfumes based on ancient recipes – such as Metopion. (CC)

UNCOVERING EGYPT’S SECRETS

The Alchemies of Scent project offers a unique perspective on the history of the ancient world and sheds light on previously unknown details about ancient Egypt. Egyptologist Diana Míčková particularly values the interdisciplinarity of the research, which has opened up entirely new perspectives for her. At times, for instance, she encounters references to plants in the temple wall inscriptions that cannot be identified without deeper knowledge of botany and chemistry.

Even when working with colleagues, reading Ptolemaic texts remains immensely challenging. In their own time, they were already written in what was effectively a dead language. “The everyday Egyptian language looked different and used different scripts, while Greek – and later Latin – served as the common language of communication in Egypt. Only a select group of priests who worked with old texts could read hieroglyphs,” Míčková explains.

These priests even developed a special hieroglyphic system known as the Ptolemaic script. It relied heavily on wordplay, pictorial riddles, acronyms, and other linguistic tricks. Those who created the system were constantly inventing new signs – while Old Egyptian had around 750 characters, Ptolemaic script boasted thousands.

This makes translation extremely demanding and time-consuming – and many texts remain untranslated. “Sometimes we understand the language but struggle to grasp the meaning. But it also gives us a fascinating opportunity to get a glimpse into the minds of the ancient Egyptians – to learn how they saw the world, what their scientific knowledge and technical methods looked like, and how these were preserved and passed on for centuries, eventually influencing the Greek and Roman societies,” Míčková adds.

And to some extent, our modern civilization still draws from them. The influence of a world more than 2,000 years removed from our own is still tangible – even in the perfume and aromatherapy industries. Just take note of how many contemporary products, with all kinds of ingredients, bear names that reference the Orient, ancient Egypt, or Queen Cleopatra herself.

*

The article first came out in the 4/2024 Czech issue of A / Magazine and in English in the 2025 English issue of A / Magazine as “Scent: The Intoxicating Power of Cleopatra.”

2025 (version for browsing)

2025 (version for download)

All Czech and English issues of A / Magazine – the official quarterly of the Czech Academy of Sciences, including its predecessor A / Science and Research – are available online.

We offer free print copies (of the Czech version and the two English issues from 2024 and 2025) to anyone interested – please contact us at predplatne@ssc.cas.cz.

Written and prepared by: Leona Matušková, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Midjourney, Wikimedia Commons, Jana Plavec, Institute of Philosophy of the CAS

The text, photos labeled CC, and the researcher profile photos are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text, photos labeled CC, and the researcher profile photos are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- Better ECGs and Industrial Superlasers – Real-World Results of CAS Research

- Czech Academy of Sciences to launch a joint-stock company

- In the Age of AI, Spotting a Fake Photo Is Harder Than Ever, Expert Says

- How to Turn Ideas into Successful Grants: The New ERC Incubator Is Offering Help

- SciComm 360° Tackled How to Communicate Science in the Age of Disinformation

- The Academy of the Future? A New Vision for Attracting Scientific Talent

- When Cars Fly and Bullets Swerve – Physics Gone Wrong on the Silver Screen

- The Academy to Boost Excellence and Careers in Research with New Programs

- Could an asteroid hit Earth? The risk is low, but astronomers are keeping watch

- At the nanoscale, gold can be blood red or blue, says Vladimíra Petráková

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Radomír Pánek started his first term of office in March 2025. He is a prominent Czech scientist specializing in plasma physics and nuclear fusion.