At the nanoscale, gold can be blood red or blue, says Vladimíra Petráková

12. 01. 2026

Using gold and diamonds, Vladimíra Petráková is working to refine optical microscopy and reveal hidden patterns in the nanoworld – while breaking Czech science stereotypes, such as women having to choose between children and a career. The scientist from the J. Heyrovský Institute of Physical Chemistry of the CAS expanded on this and more in the following interview, published in A / Magazine.

*

Do you enjoy wearing gold jewelry?

I’ve got gold earrings and a wedding ring, but you wouldn’t know it at first glance – they’re made of white gold. I can’t really wear other jewelry, since I’m allergic to certain metals.

What about a diamond necklace?

Still waiting on that one. (laughter)

Yet gold and diamonds are basically your daily bread...

They are, but I definitely don’t come across jewelry at work. What fascinates me about gold and diamonds isn’t their sparkle – it’s how they behave when they’re really, really small.

Gold in nature is often found in the form of flakes or nuggets; microscopic grains usually take on an ellipsoidal shape.

How small are we talking?

We’re in the realm of the nanoscale – particles thousands of times thinner than a human hair, smaller than the wavelength of light. And in this tiny world, gold, diamonds, and other materials behave very differently to how they would in our everyday world.

In our world, we can usually recognize gold by its color – unless, of course, it’s white gold, like your ring. Does gold look the same at the nanoscale?

Not at all! It can be blood red, but also blue, green, or purple. Its appearance depends on its size and shape – that determines which wavelength of light it interacts with the most. The most common shapes are spheres or rods, but there can also be triangles or even little stars.

So, no gold bars at the nanoscale. And I guess I shouldn’t picture a nanodiamond as a tiny cut gem either?

Definitely not cut, but it basically is a miniature piece of diamond – extremely small crystals with irregular shapes. Nanodiamonds can also come in different colors: pink, blue, yellow – it all depends on the defects inside them. Blue ones, for instance, have boron atoms in their lattice; yellow ones contain nitrogen. Pink or purple diamonds also contain nitrogen, but it’s paired with a vacancy – a missing carbon atom in the lattice. That particular defect, known as a nitrogen–vacancy center, has incredibly interesting properties that change depending on external environment.

You’ve been working with nanodiamonds since your doctoral studies. What drew you to them?

It kind of started off by chance. I had my daughter when I was twenty, and in my fifth year of university, I was looking for a job I could combine with taking care of her. I found out that doing a PhD would give me a fair amount of flexibility. That’s how I first started researching the biomedical potential of nanodiamonds – and I really got into it.

|

MOTHER OF FOUR Doing top-level research at an international standard while raising four children? For Vlaďka Petráková – who radiates boundless energy in person – it’s perfectly normal. Her daughter was born when she was twenty, and the family later grew with three sons, now aged thirteen, eleven, and five. Whether the kids will follow in her footsteps remains to be seen: “It’s that age-old story – no one’s a prophet in their own land. What Mom does isn’t as cool as what other people do. My eldest is in her first year of university studying IT. The one most interested in science might be my youngest. He got a science kit with test tubes for Christmas and was absolutely blown away,” the researcher says. |

We’ll definitely get to the topic of combining family life and science later. But first – how exactly can nanodiamonds be useful in medicine?

Nanodiamonds can serve as drug delivery vehicles for targeted therapies. They’re non-toxic, you can attach biomolecules to their surface, and they can enter cells. You can also create nitrogen–vacancy centers in them, which fluoresce. These then act as luminescent centers that don’t flicker and are incredibly stable. This makes it possible to track the nanodiamonds’ movement through cells.

Nowadays, your main focus is on gold nanoparticles. But you haven’t completely left diamonds behind, have you?

I have not. We’re still working with them, just in a different way. In one of our projects, we needed to find molecules that fluoresce in a very specific way – and nitrogen–vacancy centers turned out to be a perfect match. We want to use them to study how gold nanoparticles influence the fluorescence of nearby molecules.

Wait – are we talking about gold or diamonds here?

Both, actually. We place a gold nanoparticle next to a nanodiamond and observe how the gold affects the diamond’s glow. We jokingly describe ourselves as “nanojewelers.” (smiling)

So tell us, what’s a tiny piece of gold good for, really?

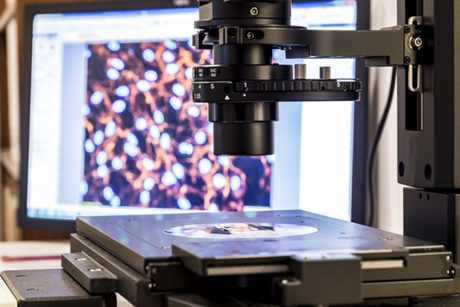

Gold has some truly fascinating properties, especially related to how it interacts with light. It can amplify the optical response of molecules, help manipulate light, and even change the light’s color or direction. Sometimes I compare it to a kind of “nanomagnifying glass” that enlarges a molecule’s image from the inside – so when we look at it under a microscope, we’re actually seeing an already magnified version. That allows us to observe finer details.

Unlike the classic golden sheen we know from jewelry, nano-gold can appear red, purple, blue, or even green. (CC)

Gold is a symbol of wealth and luxury. Is its nano form valuable too, or just regular lab material?

The value of gold nanoparticles lies more in the time and energy we put into working with them. They’re not actually that expensive. I can even give you a vial of nano-gold if you’d like. (laughter)

A vial? So it’s a liquid?

Gold nanoparticles are solid crystals, but so small that when suspended in a solution, they stay evenly dispersed and become part of the fluid. It’s called a colloidal suspension. Think along the lines of milk – that’s fat droplets in water. In the lab, we work with both gold and diamond nanoparticles in solutions.

You said gold nanoparticles are unique in how they interact with light. So what exactly happens when they “meet”?

Gold is a metal, so its lattice contains free electrons. When light passes near a gold nanoparticle, all those electrons start to oscillate in sync – and they actually extend slightly beyond the particle. This creates a dense cloud of electrons around the surface, known as a surface plasmon. The electrons oscillate at the frequency of light, so in a way, they mimic it.

And what does a plasmon do?

It acts as an amplifier. It focuses the energy of the incoming light into a tiny region near the surface of the nanoparticle. That, in turn, affects the light that’s passing through, and that’s why gold nanoparticles appear so intensely colored to us.

I guess these effects don’t happen at larger scales, do they?

That’s right. In a large piece of gold, the electrons won’t form that oscillating cloud. These effects only occur at the nanoscale, where the particles are smaller than the wavelength of light.

Nano-gold can take the form of a tiny solid particle, typically between 1 and 100 nanometers in size, that is spherical, rod-shaped, or irregular.

So gold nanoparticles act like miniature floodlights that help us see more clearly what’s happening in a sample?

That’s one way of putting it! But it only happens very close to the nanoparticle’s surface. Other fascinating effects occur in that space that we don’t fully understand yet. A few years ago, for instance, we noticed that we saw a molecule that was close to a gold particle somewhere else to where it actually was. It was a bit like a mirage – when you think you see something in one place that is somewhere else entirely.

The nanoworld clearly isn’t boring. But can this “mirage effect” be put to any use?

That’s exactly what we’re trying to figure out. We’re experimenting with this seeming motion of molecules – trying to learn how to control and use it as a more precise kind of nanomagnifying glass. It could help us determine what’s really happening inside the sample we’re observing. More detailed information on the structure and motion of molecules could make it easier to understand enzymatic reactions or DNA processes that can lead to cell damage. So there is potential for medical applications – and possibly even completely different areas, like energy research.

That’s a field quite distant from medicine. How can gold nanoparticles be useful there?

True, the applications are different, but the basic principles of how materials interact with light are the same. In some types of solar cells, for instance, nanomaterials are arranged close together, and it’s important to understand what affects how efficiently they interact with light. By grasping these fundamental principles, we can ultimately help improve solar cell performance.

Do people often ask you what your research is actually good for?

All the time. And I find it a bit tricky to answer, because what we’re doing is looking at basic principles. I compare it to exploring an unknown rainforest. You’re venturing into a place no one’s ever been to before. It’s important to keep your eyes open and try to understand and describe how this new world works. But at the same time, it’s good to think about how the findings could be useful. We’re not building new microscopes or solar panels ourselves, but even in our research we develop things that can be used in practice – for instance, we’ve created our own computer algorithms that others in different fields might find useful.

Vladimíra Petráková’s team aims to improve super-resolution microscopy to enable it to reveal even finer details.

Speaking of exploring new worlds – you spent some time living and doing research in Germany. What did that experience give you?

It was amazing in every way. It totally changed how I think about science – I felt freer, somehow. Like I had more time and energy to ask big, bold scientific questions. In the Czech Republic, I’ve always felt more overwhelmed and distracted. Maybe it’s because Germans are better organized – they plan more, so they’re not constantly getting thrown off by unexpected stuff.

Can you give an example?

Sometimes I get an email asking me to take care of a task right away or within a few days – to my liking, that kind of thing happens here too often. In Germany, everything tends to be well planned in advance, and when something urgent does come up, people give you enough time to deal with it. To me, the Czech system feels a bit too spontaneous and chaotic – and I think that can lead to a kind of passivity, where people mainly just react to requests instead of taking the initiative. Since I came back from Germany, I keep bumping into this and have to really push to carve out time for deep thinking and creativity.

But carving out time for yourself isn’t where it ends – you’ve got ambitions to change Czech science. What’s your approach?

By drawing inspiration from abroad. I want to tap into the potential of the Czech scientific diaspora. In 2018, I co-founded a platform called Czexpats in Science with two friends – we were classmates at CTU. Our organization gives researchers abroad a chance to share their experience and help improve the research environment back home. A lot of them would love to come back, but certain things are holding them back.

Do you have a sense of how many people we’re talking about and what kinds of obstacles they’re facing?

We estimate there are several thousand Czech scientists working abroad. Many of them we know are eager to stay in touch with institutions here and would like to return. They want to contribute to their fields, and personal reasons also play a role in their motivation to come back. When we asked them about the main obstacles, they pointed to a lack of transparency in hiring, salaries, and career advancement – and also academic inbreeding, meaning jobs and leadership positions going to a narrow pool of in-house graduates. We’ve mapped all of this in a report we published earlier this year.

In the publication issued by the Czexpats in Science platform, the authors ask, among other things, what changes are needed to improve cooperation with Czech researchers working abroad.

That’s the one called “Who Are the Czech Scientists Living Abroad? An Analysis of the Czech Scientific Diaspora and Its Relationship to Science in the Czech Republic”. It’s a fascinating read. What was the goal of the report?

To show how the Czech research environment is perceived from the outside, and to pinpoint areas that need improvement. I’m really pleased it has now been published. We collected data via online surveys as well as in-depth interviews. At the time of the survey, respondents were working in thirty countries around the world – three-quarters in STEM fields, and one-quarter in the social sciences and humanities.

One of the biggest issues raised – particularly by women, but also by men – was the attitude of Czech society toward women. What’s been your experience?

That issue hits very close to home. In Germany, I never once had a problem being a researcher and a mother of four. Kids there are seen as a natural part of life – and that includes your career. The institutions are set up and prepared for it. It’s a completely different story in the Czech Republic. It’s really about the overall social climate.

What do you mean by that?

Let me give you an example. I had my daughter in my first year of university. I wasn’t eligible for maternity leave, there were no social stipends, and nursery school only started at age three. I really had to fight hard just to stay in university as well as making sure my daughter was taken care of. When I tried to raise awareness about these issues, people saw me as whiny and weak. And my whole identity in other people’s eyes changed. Suddenly no one was asking me what I was passionate about or what I wanted to do after university. I was “the mom,” and everyone seemed to know exactly how I was supposed to feel, what I should be doing, and what should matter to me. That kind of environment leads many women to stay at home with their kids or settle for part-time jobs instead of going after ambitious goals – like leading their own research group.

So what needs to change for Czech science to be more open and inclusive?

A good first step is simply to acknowledge the problem and give it a name. Then you need to adjust grants and institutional policies to take life events, like having children, into account. Some institutions and grant agencies are already doing this, but the Czech research system as a whole is fragmented and lacks coordination. Through our Czexpats platform, we’re highlighting these issues. Over the past few years, we’ve professionalized – we now have our first employees and a clear vision with a plan to make it happen.

In 2018, Petráková co-founded Czexpats in Science and today serves as chair of its board.

What’s the plan, and how is it going so far?

We want Czech science to be global, open, and ambitious. We believe Czech universities belong in the world’s top 100 – and we want to help get them there. A major milestone is the report I mentioned earlier – it clearly identifies the key problems and proposes ways to address them. Another part of our work involves engaging with policymakers who can influence science policy. But we also believe strongly in grassroots efforts – supporting the scientists themselves. Together with Charles University, we launched a platform where heads of research groups can meet and share experiences. We call it the PI Forum – short for “Principal Investigator.” They can learn from each other how to lead teams, motivate coworkers, and pass on what they’ve learned, including insights from abroad.

You really lit up when you talk about Czexpats. That kind of excitement reminds me of researchers telling me stories about fieldwork in rainforests. Do you ever get opportunities in your research work to do something like that?

Though I did compare my research to exploring a rainforest, I’ll admit – it’s not quite that adventurous. (laughter) But I do find it really fulfilling. I love the variety of it, which allows for a lot of creativity. I have a dynamic research group, with its members always coming up with new ideas. We’re all different, so I’m constantly learning.

What’s your secret for building a strong team across various disciplines and cultures?

I try to keep this in mind right from the selection stage – it makes everything easier later on. We have chemists, material scientists, biophysicists – people from Germany, the UK, and Nigeria. Communication is key, and it’s important to really understand each other. Non-work activities help, too. Last year we all went on a group bike trip to Lidice. I wanted my team to connect with a piece of Czech history.

That’s a pretty intense start. The story of Lidice, destroyed and massacred by the Nazis, is deeply tragic.

All the more reason to commemorate it. I’m from Kladno, and the grammar school I attended was where the women of Lidice were held and separated from their children. It’s something that stayed with me, and I wanted to share that part of myself – and of our local history – with my team. The landscape around Lidice is actually very peaceful and delicate, so it made for a striking contrast with the place’s tragic past. And here’s a fun detail – for our colleague from Nigeria, it was a total first. He’d only sat on a bike a few times before, and this was his very first trip like that.

You ride a bike often and with joy. But as far as I know, there’s no direct bike path from Kladno to Prague, so do you take a different form of transport to get to the lab?

Unfortunately, there’s no cycle path, but I still ride my bike to work – though not every day. Sometimes it’s pretty rough. Even though I choose smaller roads, they still have traffic. I love cycling and see it not just as a great way to commute but also as a perfect means of transport for longer distances on our family vacations.

Vladimíra Petráková is an avid cyclist. She rides her bike both to work and in her free time. (CC)

Where do you and your family go cycling? And is my image correct of a peloton of bikes loaded with gear, sleeping bags, and a tent?

There’s quite a few of us, that’s true, but we’re no racers. We like to enjoy the ride through the countryside. Our favorite destination is France, which has great cycle routes and campsites. We’ve ridden along the Atlantic coast from Brittany to Bordeaux, and we’ve crisscrossed Provence and Alsace. We’d also like to visit northern Europe, but the weather there makes it a bit more challenging.

Travelling with kids comes with its own challenges. Any adventurous stories to share?

It used to be a lot about trivialities – like figuring out where to go potty – but these days it’s more about motivating the kids to push through exhaustion, get up that hill, and enjoy that sense of victory. The memory that stands out most is our very first cycling trip ten years ago. We were in France, and it rained the entire time. Everything was drenched – even the tent was waterlogged – and the final straw was when our son marched straight into a lake wearing his last pair of dry pants. I can still picture the moment the water started pouring over the tops of his wellies. At that point all I wanted to do was cry. But he loved it, and now it’s one of our fondest memories. (laughter)

Exploring the nanoworld must be intense work, so I can see why cycling would be a great way to clear your head. How else do you relax?

I quite enjoy running, too. I have a dream of doing this race in New Zealand that goes all the way across the island from one coast to the other. It’s a mix of running, biking, and kayaking. When I turned thirty, I told myself I’d do it at forty. Well, I’m turning forty this year, and I’m definitely not ready yet. I’ll have to step up my game. (laughter) Maybe next year. For now, it’s still up in the air.

Speaking of skies – this January, your team published a paper in Nature Communications that surprisingly connects with stars a little, doesn’t it?

Yes. We use fluorescence to visualize molecules, so what we see under the microscope resembles a starry sky: a black background with lots of glowing dots. We took inspiration from a technique used in astronomy and adapted it to help identify molecules in microscopic images.

|

SUPERGLASSES THAT ZOOM IN REALLY CLOSE For a long time, it was considered a given in the scientific world that optical microscopes had a hard limit due to the physical properties of light (the so-called Abbe diffraction limit). These barriers were only broken through recently. In 2014, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Americans Eric Betzig and William E. Moerner and German scientist Stefan W. Hell for discoveries that led to the development of super-resolution optical microscopy. We covered the evolution of these new microscopy techniques in the 2024 English issue of A / Magazine, in a special feature on light. |

How did you come up with that idea?

This method has long been used in astronomy and radar systems, but oddly enough, not in microscopy. The idea came from my colleague Miroslav Hekrdla, who used to work in radar research. I think it’s a brilliant example of how ideas from one field can spur advances in another. There truly is strength in diversity.

That diversity seems to run through your entire scientific path. Which field would you say you actually belong to – physical chemistry, biophysics, materials engineering?

Originally, at the Czech Technical University in Prague, I studied biomedical engineering, which deals with hospital technologies, ultrasounds, MRI, and so on. It gave me a solid grounding across disciplines – I learned physics, chemistry, electronics, signal processing, as well as biology and the basics of medical subjects. Our whole team is interdisciplinary, which allows us to approach our research from unconventional perspectives.

So that’s why you see potential in gold and diamond nanoparticles that might not be obvious at first glance…

There’s still a lot to uncover – the nanoscale world is largely unknown, like those metaphorical jungles we talked about earlier.

*

|

Assoc. Prof. Ing. VLADIMÍRA PETRÁKOVÁ, Ph.D.

Vladimíra Petráková studied biomedical engineering at the Czech Technical University in Prague. During her PhD, which she completed in part at the Institute of Physics of the CAS, she researched luminescent centers in diamonds. Between 2016 and 2019, she worked at the Free University of Berlin, where she began focusing more on gold nanoparticles. Her goal is to describe what happens when gold nanoparticles interact with light, and how this could be used to enhance optical microscopy. In 2021, Petráková received a Junior Star grant from the Czech Science Foundation, followed by the Lumina Quaeruntur Award from the Czech Academy of Sciences in 2022. She is also a co-founder of Czexpats in Science, a platform connecting Czech researchers abroad and advocating for the positive transformation of the Czech scientific system. |

*

The interview first came out in the 1/2025 Czech issue of A / Magazine and in English in the 2025 English issue of A / Magazine:

2025 (version for browsing)

2025 (version for download)

All Czech and English issues of A / Magazine – the official quarterly of the Czech Academy of Sciences, including its predecessor A / Science and Research – are available online.

We offer free print copies (of the Czech version and the two English issues from 2024 and 2025) to anyone interested – please contact us at predplatne@ssc.cas.cz.

Written and prepared by: Leona Matušková, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

The text and photos marked CC (and the researcher's bio photo) are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text and photos marked CC (and the researcher's bio photo) are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- Czech Academy of Sciences to launch a joint-stock company

- In the Age of AI, Spotting a Fake Photo Is Harder Than Ever, Expert Says

- How to Turn Ideas into Successful Grants: The New ERC Incubator Is Offering Help

- SciComm 360° Tackled How to Communicate Science in the Age of Disinformation

- The Academy of the Future? A New Vision for Attracting Scientific Talent

- When Cars Fly and Bullets Swerve – Physics Gone Wrong on the Silver Screen

- The Academy to Boost Excellence and Careers in Research with New Programs

- Could an asteroid hit Earth? The risk is low, but astronomers are keeping watch

- The beauty of Antarctic algae: What can diatoms tell us about climate change?

- Moss as a predator? Photogenic Science reveals the beauty and humor in research

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.