A little-known chapter of history: Czechoslovaks who fought in the Wehrmacht

05. 12. 2025

Even eighty years after the end of World War II, stories locked away in the recesses of memory are still coming to light – like the overlooked past of the many thousands of Czechoslovaks who served in the German army. “We tend to see World War II in fixed images that we consider unquestionable and reflective of reality. But it turns out it’s not that simple,” historian Zdenko Maršálek stresses. The phenomenon of non-German soldiers serving in the Wehrmacht reveals just how much our perception of the past can be shaped artificially. The article came out in the A / Magazine of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

Otmar Malíř was fifteen when Polish forces occupied his native region of Těšín Silesia in 1938, and sixteen when the Germans took over the same territory in 1939. The Silesian region around the towns of Těšín (Cieszyn, Teschen), Jablunkov, and what is now Havířov historically developed at the intersection of Polish, Czech, and German cultures. It belonged to Czechoslovakia during the years between the two world wars, yet its inhabitants maintained a distinct identity that defied traditional notions of nationality. Most locals spoke (and some still speak) “po naszymu [our way],” a dialect that sounds like a blend of Polish and Czech.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, it seized control of the Silesian Voivodeship, which included the Těšín Silesia region. As in other annexed Polish territories, the Nazis introduced the so-called Deutsche Volksliste – a register of inhabitants deemed suitable for Germanization. Refusing to sign could result in harsh reprisals, including imprisonment in a concentration camp. Signing the Volksliste conferred certain rights – graded by category – such as permission to remain in one’s homeland and keep a job, property, or land. The flip side was the obligation for men to enlist in the German army.

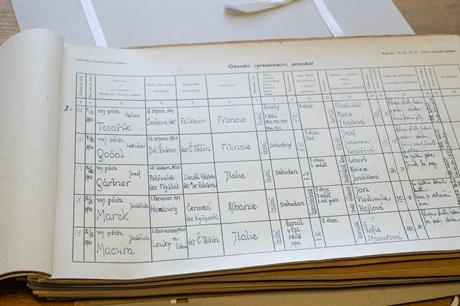

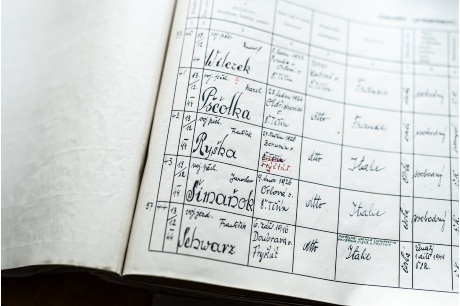

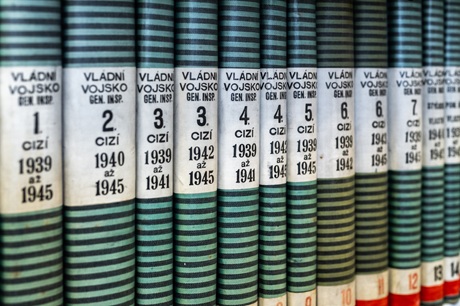

Draft records of soldiers joining the Czechoslovak army-in-exile reveal that a large number of them had previously served in the Wehrmacht. (CC)

The aforementioned Otmar Malíř received his call-up papers for the Wehrmacht in September 1942. After the war, he recalled planning to desert the German army from the start and join the Allies. He got his chance soon enough – while serving in the Afrika Korps, the Wehrmacht force fighting in North Africa, he was captured by the British in May 1943. Together with several friends from Těšín Silesia, he plucked up the courage to approach the guards and declare that they were not Germans and wanted to switch sides.

“Without a doubt, one of the first people to break the long silence surrounding the participation of Czechoslovaks in the Wehrmacht was Otmar Malíř. He was a patriot who had already stood up for the Czech cause during the Polish occupation, deserted the Wehrmacht at the first opportunity, and joined the Czechoslovak army in exile,” says military historian Zdenko Maršálek from the Institute of Contemporary History of the Czech Academy of Sciences (CAS).

MURKY STATISTICS

The story of Malíř may be the first to have been recorded, but it’s far from typical. “You can’t generalize. There were so many individual fates, and each one was completely different. Not every Czechoslovak who served in the Wehrmacht joined the Czechoslovak forces after being captured. Most spent the entire war in a German uniform,” the historian adds.

Zdenko Maršálek from the Institute of Contemporary History of the CAS. (CC)

Statistics do little to clarify the situation. Precise figures on how many Czechoslovak citizens were drafted into the Wehrmacht simply don’t exist – we only have estimates. It’s clear, though, that by far the greatest number of conscripts came from among Czechoslovak Germans, be they from the annexed Sudetenland or the Protectorate. The total may have reached as many as three-quarters of a million people. After the war, the vast majority of them were expelled to Germany.

The picture is different, however, for Těšín Silesia, where roughly 23,000 men were gradually conscripted, and for the Hlučín (Hultschin) Region, which saw about 13,000 locals join the Wehrmacht. Both regions were returned to Czechoslovakia after the war and remain part of the Czech Republic today. Most local residents were not expelled because they were not ethnic Germans. This left thousands of men with wartime experience on the German side living in postwar Czechoslovakia.

PRUSSIAN HLUČÍN REGION

Franz Kalwar, a 23-year-old from Darkovice near Hlučín, was working in an iron ore mine in the German town of Eiserfeld when the war broke out. Not long afterward, he was called up from nearby Siegen. He served with the infantry in several locations, including Finland, where he took part in Operation Arctic Fox – part of the German assault on the Soviet Union. Franz was wounded there, and – as his family later recalled – was lucky to encounter a doctor he knew from before, who issued him a certificate stating that he was unfit for further military service.

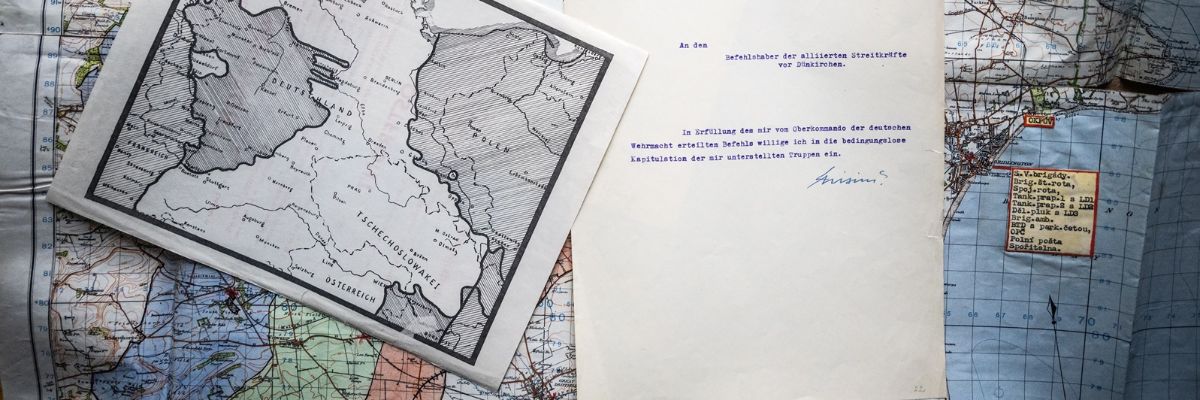

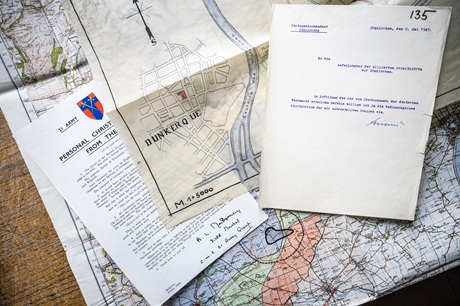

Maps showing the front lines, written orders, correspondence of ordinary soldiers as well as military leaders – these are the kinds of materials historians rely on for research.

By July 1942, Franz was back in the mines of Eiserfeld. He made it back to his home village of Darkovice several months after the war ended. His story is one of around 11,000 more or less documented accounts of men from Hlučín who fought in the Wehrmacht, preserved in the online database of the Hultschiner Soldaten project.

The Hlučín Region – bounded roughly by the cities of Opava, Ostrava, and Bohumín – has a different history from neighboring Těšín Silesia. For nearly two centuries, from 1742 to 1920, it was part of Prussia. The local Slavic population retained close ties to German language and culture even during the interwar period. To this day, the villages in the region are dominated by churches built in the typical Prussian style of bare brickwork, and the locals are still known in surrounding areas as Prajzáci, derived from Preußen (Prussians).

There are some in the Hlučín Region who even welcomed the German arrival in 1939 with enthusiasm. But soon enough, even those who didn’t share their neighbors’ joy were forced to enlist in the Wehrmacht. Of the 13,000 local men who served, roughly one in five never returned.

TURNCOATS

For Wehrmacht soldiers who ended up in the Czechoslovak army in exile, the path typically led through Allied captivity – whether they actively defected across the front or simply allowed themselves to be captured. Over the course of the war, around 250 men from the Hlučín Region and more than 2,000 from Těšín Silesia swapped the German uniform for a Czechoslovak one.

Draft-records for the Czechoslovak army in exile list each soldier’s name, rank, and place of birth, as well as where he was recruited. The men shown in the table above joined the Czechoslovak army after being taken prisoner on the Italian front.

Strikingly, more than 61 percent of all former Wehrmacht troops who were assigned during the war to Czechoslovak units in the West came from just two small districts – 786 men from the Český Těšín District and 1,009 from the Fryštát District.

Historian Zdenko Maršálek came across the fates of these men in the German uniform while examining archival records related to the Czechoslovak armies in exile in the West. “We were compiling a database of all members of the Czechoslovak forces in exile, and it was a genuine shock to us once we realized how many of them had served in the Wehrmacht prior to joining the Czechoslovak units,” he says.

This is also because the subject had been taboo for fifty or sixty years after the war – it wasn’t taught in schools, and no systematic research had been done. It’s worth noting that this wasn’t just a Czech phenomenon. “We see similar stories in many European countries that bordered Germany and experienced occupation and the annexation of parts of their territory into the Reich,” Maršálek points out.

Forced conscription was a shared fate in regions like Alsace and Lorraine in France, Carniola in Slovenia, Upper Silesia in Poland, or the area around Eupen and Malmedy in Belgium. In all these regions, historians and journalists only began tackling the topic many decades after the guns had fallen silent.

BREAKING DOWN BLACK-AND-WHITE NOTIONS

“We tend to see World War II in fixed images that we consider unquestionable and reflective of reality. But more and more, it turns out it’s not that simple,” Maršálek stresses. The phenomenon of non-German soldiers serving in the Wehrmacht reveals just how much our perception of the past can be shaped artificially.

That this chapter of history is only now coming to light is, in a way, understandable. After the war, there was a need to rebuild faith in the future, and the focus was mainly on stories of heroism and brave, direct resistance to Nazism. The fact that hundreds of thousands of citizens from Allied countries fought on the enemy’s side didn’t fit that narrative. “If there had only been a few, they might have been dismissed as contemptible collaborators. But the number of people who served in the Nazi forces was relatively high across all Allied countries,” the historian adds.

These former Wehrmacht soldiers returned home without fanfare. Their future was uncertain. In most areas, including Těšín Silesia and the Hlučín Region, a kind of unwritten social contract was eventually reached between the state and its citizens: the regime granted them a general pardon and left them in peace, and in return, they “forgot” their past and refrained from speaking about it publicly.

The Central Military Archive in Prague holds thousands of records documenting the fates of Czechoslovak citizens.

Today’s renewed focus on the topic is a generational matter. Grandchildren, now grown up, are asking questions about the fate of their grandfathers who had served in the Wehrmacht. Their own parents, however, often know very little about it. Until the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 – and even for several years after – it was a locked room no one dared open. Although in the regions affected, practically every family had been touched by the experience, it was rarely spoken of.

Otmar Malíř was one of the few who wrote down their personal memories. Others buried the past deep within themselves and had no desire to revisit it. Many untapped sources can still be found in archives across Europe. And perhaps additional compelling testimonies will surface within families too – now, after so many decades, the right time may finally have come. Maybe somewhere in your attic or cellar, there too is an unexpected relic from a grandfather, great-grandfather, or distant relative who had once served in the German army.

|

Mgr. et Mgr. Zdenko Maršálek, Ph.D.

His parents, both mathematicians, had hoped he would become a statistician or economist. But Zdeno Maršálek was always drawn more to words and images than to numbers. After a brief career as an art teacher, he studied history following the Velvet Revolution in 1989. He worked at the History Institute of the Army of the Czech Republic and the Central Military Archive in Prague; since 2006, he has been a research fellow at the Institute of Contemporary History of the CAS. He is the author of the book “Česká’’, nebo “československá’’ armáda? Národnostní složení československých vojenských jednotek v zahraničí v letech 1939–1945 (A “Czech” or “Czechoslovak” Army? The Ethnic and Nationality Composition of the Czechoslovak Military Units-in-Exile in 1939–1945) and co-author of Dunkerque 1944–1945. His forthcoming book V uniformě nepřítele. Čechoslováci a služba ve wehrmachtu (In the Enemy’s Uniform: Czechoslovaks and Conscription in the Wehrmacht) is due out in 2026. |

AUTHOR’S NOTE

He was sixteen when he was drafted. My grandfather, Gustav Heczko, was one of those whose life was shaped by the forces of history more than he would have liked. That’s why the subject of this article hits far closer to home than any other. Reading through the few testimonies I found from the men of Český Těšín, I was deeply affected. “There were piles of winter coats covered in blood. They must have been uniforms from dead soldiers. We had to put them on quickly. We were just kids. Nothing fit, everything was too big. I got a pair of boots that were about to fall apart,” recalls František Bocek from Bukovec near Jablunkov in the Paměť národa (Memory of Nations) project, describing his induction into the German army in 1944. The same birth year, same draft year, and practically the same hometown as my grandfather. Did they know each other? Did they endure the same horrors? I can no longer ask my grandfather. By the time he started opening up about his wartime experience, I didn’t record or write anything down. Back then I was too shy to ask if I could. My grandmother’s older brother also served in a German uniform – but he never made it back home to Karviná. My father doesn’t recall his parents ever speaking about the past; they lived in the present. Just like in many other families with similar fates, the war story in ours remains a taboo.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

You can find more information on this topic on the Czechs in the Wehrmacht website of the Institute of Contemporary History of the CAS.

Visiting one of the regional museums in the Czech Republic could also be illuminating, for example the Hlučín Region Museum, the Silesian Museum, or the Těšín Silesia Region Museum.

The photos for this article were taken within the premises of the Central Military Archive in Prague.

The English article first came out in the 2025 issue of A / Magazine of the CAS as “In the Wehrmacht Uniform.”

2025 (version for browsing)

2025 (version for download)

All Czech and English issues of A / Magazine – the official quarterly of the Czech Academy of Sciences, including its predecessor A / Science and Research – are available online.

We offer free print copies (of the Czech version and the two English issues from 2024 and 2025) to anyone interested – please contact us at predplatne@ssc.cas.cz.

Written and prepared by: Leona Matušková, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS; Shutterstock

The text, photos marked CC, and the researcher's profile photo are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text, photos marked CC, and the researcher's profile photo are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- Light vs. Antibiotics – Can We Get Harmful Substances Out of Our Water?

- Better ECGs and Industrial Superlasers – Real-World Results of CAS Research

- Czech Academy of Sciences to launch a joint-stock company

- In the Age of AI, Spotting a Fake Photo Is Harder Than Ever, Expert Says

- How to Turn Ideas into Successful Grants: The New ERC Incubator Is Offering Help

- SciComm 360° Tackled How to Communicate Science in the Age of Disinformation

- The Academy of the Future? A New Vision for Attracting Scientific Talent

- When Cars Fly and Bullets Swerve – Physics Gone Wrong on the Silver Screen

- The Academy to Boost Excellence and Careers in Research with New Programs

- Could an asteroid hit Earth? The risk is low, but astronomers are keeping watch

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Radomír Pánek started his first term of office in March 2025. He is a prominent Czech scientist specializing in plasma physics and nuclear fusion.