The beauty of Antarctic algae: What can diatoms tell us about climate change?

05. 01. 2026

You can find them in Czech ponds just as in the Nile or the Amazon, and in seas and oceans, too. Diatoms (microalgae) are highly adaptable and thrive almost everywhere – including in the extreme environment of Antarctica. In January 2025, biologist Kateřina Kopalová headed straight into the kingdom of ice to study them in situ. How challenging is it to go on an Antarctic expedition, and what makes diatoms so remarkable? We wrote about the researcher’s adventures in the 2025 English issue of A / Magazine, the official quarterly of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

Snow-white ice floes dot the surface of the sea and look like scattered building blocks from above. The sun is shining, and the sky is a brilliant blue. It’s January 2025, high summer in Antarctica, with long polar daylight and temperatures hovering around zero. Ideal conditions for landing near the research base bearing the optimistic name Esperanza (Hope), located at the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, not far from a huge penguin colony.

“The weather really played into our hands this time. But it must be said that every trip to Antarctica is extraordinary. The landscape there just sweeps you away. The vastness, the silence, the pristine wilderness – everything there takes on a life of its own,” recalls polar ecologist Kateřina Kopalová over coffee in Prague. A researcher at the Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Faculty of Science at Charles University, Kopalová has already visited the southernmost continent five times. But in many respects, this year’s expedition was exceptional.

Kateřina Kopalová is a researcher at the Institute of Botany of the CAS and the Faculty of Science at Charles University. (CC)

Until now, the ecologist had always stayed on the surrounding islands. This year, for the very first time, she set foot directly on the Antarctic mainland. Unlike previous expeditions, she was not the only Czech in the Argentinian team and, for the first time in the southern land of ice and snow, she also played the viola. But let’s start at the beginning – Kopalová’s scientific journey was anything but straightforward.

FROM SETBACKS TO SUCCESS

As often happens in science, Kopalová stumbled onto her research topic – Antarctic diatoms – practically by accident. She had wanted to work on something related to water; during her undergraduate studies, she was tempted by research of lakes in the Pyrenees, for example. But around twenty years ago, the first samples from Antarctica arrived at the Department of Ecology where she was studying.

At that time, preparations were in full swing for building the Czech research station on James Ross Island, and the number of Czech scientists there was growing. They were exploring sites where virtually no one had done research before, and they were bringing back unique samples to be studied in Prague.

There are several research stations in Antarctica. Although the J.G. Mendel Czech Antarctic Station, operated by Masaryk University in Brno, has been active here since 2007, Kateřina Kopalová has worked primarily with Argentine scientists throughout her research career.

“I thought to myself: I don’t know anything about diatoms, but Antarctica sounds amazing. So I said yes to the offer. I grabbed the first European atlas of algae I could find and started identifying Antarctic samples under the microscope,” Kopalová says with a laugh today. “Of course, at the beginning I misidentified almost all of them. It was like trying to recognize birds in Africa using a Czech ornithological handbook.”

These early setbacks only spurred her onward. At an international conference, Belgian diatom specialist Bart Van de Vijver noticed the young student’s enthusiasm and offered Kopalová an opportunity to work together. She left to Belgium for a research fellowship and later spent part of her doctoral studies at the University of Antwerp.

Together with her Belgian supervisor and other colleagues, she began systematically analyzing available algal samples and set out herself to collect more in Antarctica. Altogether they described dozens of new species. The result was a completely new identification atlas of freshwater diatoms for the Antarctic Peninsula and nearby islands, published in 2016.

Kateřina Kopalová in the lab facilities at the Esperanza research base in January 2025.

JEWEL-LIKE GLAMOR

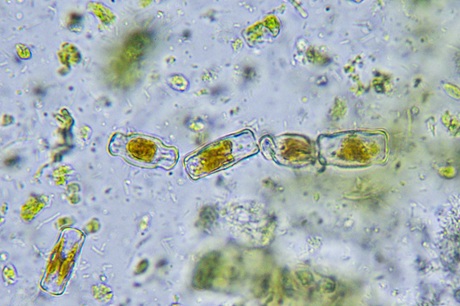

Diatoms are fascinating microorganisms. They can photosynthesize, they live in the waters of almost every environment on Earth, and they are capable of adapting to extreme conditions. They form the foundation of freshwater and marine food chains and are also used, for instance, in routine water-quality monitoring and forensic analysis. While diatoms in other regions, including Central Europe, have been fairly well studied, Antarctic diatoms have until recently received far less attention.

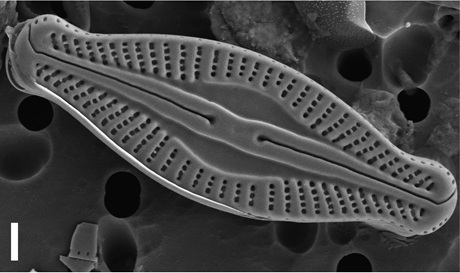

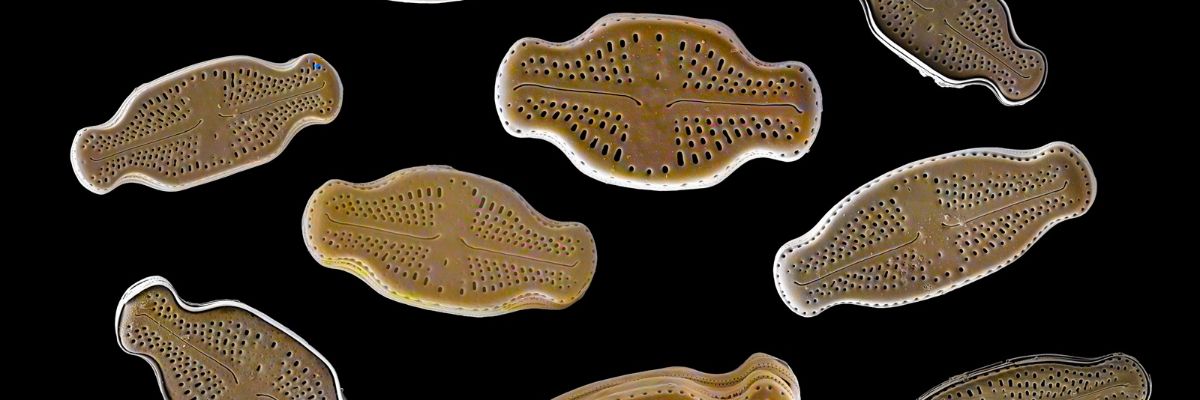

As Kopalová explains, diatoms are basically tiny plants encased in intricate glass (silicate) shells of every imaginable geometric shape and pattern. Under an electron microscope, you can distinguish the fine ornamentation on their silica frustules. “I find it incredible that something so minuscule can be so perfectly crafted. They’re simply beautiful,” the ecologist says.

Her favorite is the genus Luticola, an exceptionally species-rich group of diatoms. They can be found in lakes, wetlands, moss, and damp soils, and they are among the most diverse diatom genera in Antarctica. Another of Kopalová’s favorites is Microcostatus naumannii (Hustedt) Lange-Bertalot. “I love the way it looks, even though it’s not a particularly rare species. You can recognize it under the microscope right away, unlike many other Antarctic diatoms,” the researcher says.

|

HOW A DIATOM GETS ITS NAME |

INTO THE FIELD

Kopalová collected her first research samples in 2011. Since 2007, James Ross Island has hosted the J.G. Mendel Czech Antarctic Station, operated by Masaryk University in Brno, but the biologist headed instead to another part of the island, independent of the Czech base. Thanks to a joint project with the Argentine Antarctic Institute, she began working with Argentine scientists, who, given their country’s geographic position, have the closest access to Antarctica. That very first expedition, however, proved to be a serious trial: practically everything that could possibly go wrong, did.

The weather was relentlessly against them, and the aircraft broke down, so the originally planned six-week trip stretched to almost three months. “We ended up spending Christmas and New Year in Antarctica. To make matters worse, I didn’t speak any Spanish at the time, and the Argentinians weren’t fluent in English, so communication was tricky. And I was the only woman there among about a hundred soldiers,” Kopalová notes with a laugh.

Unpredictability is characteristic of fieldwork in Antarctica. Nothing can be taken for granted – the climate can foil even the best-laid plans. But once you come to terms with this, you can enjoy the journey to the fullest. Alongside her rough first experience, the polar ecologist has a trove of amazing memories and powerful encounters – with both breathtaking nature and the people she has met there.

Antarctica is on average the coldest, windiest, and driest of all continents – and is sometimes called the world’s largest desert.

DIATOMS ARE NO WHALES

Today, Kopalová is at home in Antarctica and even acts as a guide for fellow scientists and adventurers. Such as this past January, when she brought along photographer and science communicator Petr Jan Juračka, whom she has known since their first year at university. A passionate traveler, Juračka once mentioned to her he had visited every continent except Antarctica. So she arranged with her Argentine colleagues to bring him along this time, to document their local research and share it with the public.

What for her has become almost routine, Juračka experienced with the wide-eyed wonder of a child. He photographed and filmed everything that caught his attention. Thanks to his perseverance – waiting for the perfect shot even to the point of nearly freezing – he returned from Antarctica with stunning images and videos of penguins, seals, sea lions, giant kelp, and cormorants.

“As a microbiologist, I’m usually knee-deep somewhere in the mud, but when I get the chance to watch penguins and sea lions in their natural habitat, I’m thrilled. The absolute highlight, though, was Petr’s drone footage of humpback whales – I had never seen whales so beautifully before,” Kopalová notes, praising her friend’s work.

What is it like to work in a penguin paradise? Kateřina Kopalová’s expedition was captured on camera by Petr Jan Juračka.

Diatoms are no whales or penguins, but for the polar ecologist, they are an endlessly fascinating subject of research. From the start, she has approached diatoms from two angles: first, identifying and classifying Antarctic species and mapping their distribution (taxonomy and biogeography), and second, studying them ecologically as model organisms within the ecosystem.

TEST TUBES IN THE FRIDGE

On her trips to Antarctica, Kopalová tries to cover as many locations as possible, which is why she always sets out for a different area. She has explored ponds and streams on Seymour and James Ross Islands and in the South Shetlands. Only this year did she finally make it to the mainland itself – specifically, the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. She collects samples either on her own or together with other scientists from various disciplines. Some focus on the geological bedrock, others on the chemical and physical properties of lakes or on climate conditions.

Diatoms generally live in lake sediments and can be found on stones, in sand, and in mud; some species thrive in damp moss or on wet rock faces. They also occur in cryoconite holes – i.e., little glacier depressions filled with dust. The best time for collecting samples in Antarctica is during the austral summer, which usually corresponds to January and February. Temperatures hover around 0 °C, and if the icy wind isn’t blowing, conditions allow you to move about fairly comfortably.

In the field, Kopalová places samples of diatoms taken from sand, mud, or moss into test tubes, and from a single Antarctic expedition she usually brings home around three hundred of them, stored in camping coolers. Back in Prague, this is followed by months and years of painstaking study.

Microscopic diatom algae, occurring in both freshwater and marine ecosystems, are excellent indicators of water quality.

For three hundred years, scientists have identified diatoms mainly by the appearance of their silica shells. Microscopy remains the cornerstone of this research, but molecular methods are playing an ever more important role. “There’s a lot of cryptic diversity among diatoms. That means they may look identical at first glance, and even at the microscopic scale we can’t tell the difference, but DNA sequencing reveals they’re actually different species,” the biologist explains. As a result, algal checklists are constantly being revised and refined, while a digital molecular library of algae species is being built at the same time.

MELTING GLACIERS AND THE FUTURE

For polar ecologists, diatoms are an ideal model organism, and Antarctica an ideal model ecosystem. Its advantage lies in its simplicity – very little can survive in such extreme conditions. Life is found there mainly in the form of microorganisms; mammals and birds only make use of the land temporarily, mostly during breeding season.

Because of the relative simplicity of environmental conditions, the consequences of climate change – especially the effects of global warming – can be observed in Antarctica almost in real time. For instance, in 2021, meteorologists recorded temperatures of over 18 °C at the Esperanza Base, whereas the average summer temperatures there usually range from –2 to +5 °C.

Rising temperatures affect ice shelves (floating slabs of ice), which break up under melting temperatures and in turn destabilize the continental glaciers behind them. The first colonizers of the newly ice-free ground are microorganisms, including diatoms. Studying in detail how they spread makes it possible to better understand the colonization of new soils – both in Antarctica and more generally in warming environments alike.

Scientists can thus model how climate change will shape not only Antarctica, but also, for instance, Europe. In a few decades, it is expected that all Alpine glaciers will melt, creating new expanses of ice-free land. Thanks to this research, we can already anticipate which microorganisms will colonize them and how the associated changes in hydrological conditions will transform the environment.

STRINGS IN THE WIND

Whereas Kopalová’s first Antarctic expedition fourteen years ago didn’t go entirely according to plan, this year, it was a success beyond expectations. She returned to Prague with nearly thirty kilograms of samples for her team to study in the coming years, while Juračka brought back home gigabytes of unique photos and video footage. Their joint journey resulted in a series of documentary vlogs on YouTube, several popular science articles, and a lecture tour of Czech cinemas and cultural centers, bringing audiences both the beauty of Antarctica and the behind-the-scenes reality of conducting research in extreme conditions.

Kateřina Kopalová with Petr Jan Juračka, the author of all the photos in this article taken in Antarctica.

This latest expedition differed from the earlier ones in one other way, too. Packing for the Antarctic terrain is always demanding, and you only bring what is absolutely essential to stay warm and collect your samples in peace. This time, however, Kopalová decided to take something you wouldn’t expect to find in the backpack of a polar ecologist – a viola, her lifelong companion, which almost led her to an alternate career path.

Bringing it along was a slightly mad idea, but it fit perfectly with the spirit of an extraordinary expedition. It allowed the researcher to combine her two passions – music and Antarctica – and tuxedoed penguins got the rare chance to sway to the sounds of Antonín Dvořák. “It was a challenge to tune the viola in the cold, and after a while my fingers were freezing, but otherwise, I enjoyed it immensely. The most beautiful moment came when we held the instrument in the wind, which began producing its own sounds against the strings. Once again it became clear that Antarctica lives a life all its own,” Kopalová recalls with a laugh.

|

Mgr. KATEŘINA KOPALOVÁ, Ph.D.

The decision whether to become a professional violist or a scientist was settled by Kateřina Kopalová’s first Antarctic expedition during her doctoral studies at the University of Antwerp in Belgium. The musician path may have fallen by the wayside, but Kopalová hasn’t abandoned her viola. In her spare time, she plays in the Malá Strana Chamber Orchestra and has performed in orchestras in Belgium and during her postdoctoral stay at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her professional passion lies with diatoms – microscopic algae with silica shells that occur in countless geometric shapes. In 2022, she co-founded the research group DiCE (Diatoms in Cryospheric Ecosystems) at the Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science (Charles University). She is the recipient of the Charles University Bolzano Award, and in 2024, Kopalová also won the prestigious L’Oréal–UNESCO For Women in Science award. |

*

The article first came out in the 2/2025 Czech issue of A / Magazine and in English in the 2025 English issue of A / Magazine as “Beauties from the Kingdom of Ice.”

2025 (version for browsing)

2025 (version for download)

All Czech and English issues of A / Magazine – the official quarterly of the Czech Academy of Sciences, including its predecessor A / Science and Research – are available online.

We offer free print copies (of the Czech version and the two English issues from 2024 and 2025) to anyone interested – please contact us at predplatne@ssc.cas.cz.

Written and prepared by: Leona Matušková, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Petr Jan Juračka (photos from Antarctica); Kateřina Kopalová (diatom photos); Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

The text and photos marked CC (and the researcher's bio photo) are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text and photos marked CC (and the researcher's bio photo) are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- Czech Academy of Sciences to launch a joint-stock company

- In the Age of AI, Spotting a Fake Photo Is Harder Than Ever, Expert Says

- How to Turn Ideas into Successful Grants: The New ERC Incubator Is Offering Help

- SciComm 360° Tackled How to Communicate Science in the Age of Disinformation

- The Academy of the Future? A New Vision for Attracting Scientific Talent

- When Cars Fly and Bullets Swerve – Physics Gone Wrong on the Silver Screen

- The Academy to Boost Excellence and Careers in Research with New Programs

- Could an asteroid hit Earth? The risk is low, but astronomers are keeping watch

- At the nanoscale, gold can be blood red or blue, says Vladimíra Petráková

- Moss as a predator? Photogenic Science reveals the beauty and humor in research

Contacts for Media

Markéta Růžičková

Public Relations Manager

+420 777 970 812

Eliška Zvolánková

+420 739 535 007

Martina Spěváčková

+420 733 697 112